| Element | |

|---|---|

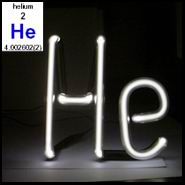

2HeHelium4.00260222

|

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 2 |

| Atomic weight | 4.0026022 amu |

| Element family | Nobel gases |

| Period | 1 |

| Group | 18 |

| Block | s-block |

| Discovery year | 1868 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

3He 0.000138% 4He 99.999862% |

4He (100.00%) |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 0.0001785 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | -272.2 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Boiling | -268.9 °C |

Helium (He) -268.9 Tungsten (W) 5927 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| First ionization potential | 24.587 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | -0.500 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Atomic radius | |

|---|---|

| Covalent radius | 0.46 Å |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 0.32 Francium (Fr) 2.6 | |

| Van der Waals radius | 1.4 Å |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 1.2 Francium (Fr) 3.48 | |

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 2 |

| Electronic configuration | 1s2 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 2 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

Helium (He): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

Helium (He), atomic number 2, represents the first noble gas and second lightest element in the periodic table with standard atomic weight 4.002602 ± 0.000002 u. This monatomic gas exhibits complete chemical inertness under standard conditions, characterized by a filled 1s² electron configuration. Helium demonstrates unique quantum mechanical properties including superfluidity in its liquid phase below 2.17 K and remains the only element that cannot be solidified at atmospheric pressure. Industrial applications encompass cryogenic cooling systems, particularly in superconducting magnets for MRI scanners, pressurization systems, and specialized breathing mixtures for deep-sea diving operations.

Introduction

Helium occupies position 2 in the periodic table as the lightest noble gas and exhibits exceptional chemical stability due to its complete 1s² electronic configuration. The element demonstrates fundamental significance in quantum physics research, particularly in studies of superfluidity and low-temperature phenomena. Discovered spectroscopically in the Sun's chromosphere by Pierre Janssen in 1868, helium was later isolated terrestrially by William Ramsay in 1895 through mineral uranium decay processes. This noble gas represents approximately 0.00052% of Earth's atmospheric composition but constitutes roughly 23% of the observable universe's elemental mass, being produced primarily through stellar nucleosynthesis processes.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Helium exhibits atomic number Z = 2 with electron configuration 1s², representing the first completed electronic shell in the periodic table. The atomic radius measures 31 pm (van der Waals radius 140 pm), making helium the smallest neutral atom. Effective nuclear charge experienced by valence electrons equals +2, with minimal shielding effects due to the absence of core electrons. First ionization energy demonstrates exceptionally high value at 2372.3 kJ/mol, reflecting the strong nuclear attraction on the 1s electrons. Second ionization energy reaches 5250.5 kJ/mol, corresponding to removal of the remaining electron from He⁺ species. Helium exhibits zero electron affinity, consistent with its filled shell configuration and chemical inertness.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

At standard temperature and pressure, helium exists as a colorless, odorless monatomic gas with density 0.1786 g/L at 273.15 K. The element exhibits extremely low boiling point at 4.222 K (-268.928°C) under atmospheric pressure, representing the lowest boiling point of all elements. Helium demonstrates no triple point at atmospheric pressure and cannot form solid phase below 25.07 bar pressure. Critical temperature reaches 5.1953 K with critical pressure 2.2746 bar and critical density 69.58 kg/m³. Liquid helium manifests two distinct phases: helium I (normal fluid above 2.1768 K) and helium II (superfluid below this lambda temperature), with the latter exhibiting zero viscosity and infinite thermal conductivity.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

Helium's 1s² configuration represents the most stable electronic arrangement possible for a two-electron system, resulting in complete chemical inertness under all normal conditions. The filled s orbital exhibits spherical symmetry with maximum electron density at the nucleus, contributing to helium's exceptional ionization energy. No stable chemical compounds of helium have been definitively characterized, though theoretical calculations suggest potential formation of metastable species such as HeH⁺ under extreme conditions. Van der Waals interactions between helium atoms remain exceptionally weak, with polarizability α = 0.205 × 10⁻⁴⁰ C·m²/V, explaining the element's gaseous state persistence to extremely low temperatures.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Helium exhibits no measurable electronegativity on conventional scales due to its complete electronic shell configuration. Standard electrode potential cannot be defined for helium owing to its chemical inertness and inability to form ionic species in aqueous solution. Thermodynamic stability of helium atoms exceeds that of any potential compounds, with calculated formation energies for hypothetical helium compounds invariably positive. The element demonstrates remarkable resistance to plasma formation, requiring electron impact energies exceeding 24.6 eV for ionization, among the highest values in the periodic table.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

No stable binary compounds of helium exist under standard laboratory conditions. Theoretical investigations suggest that extreme pressures exceeding 200 GPa might stabilize compounds such as Na₂He, but experimental confirmation remains absent. Matrix isolation techniques have enabled spectroscopic detection of weakly bound van der Waals complexes including He₂⁺ and HeH⁺ ions at cryogenic temperatures, though these species decompose readily upon warming. Fullerene complexes such as He@C₆₀ demonstrate physical entrapment rather than chemical bonding, with helium atoms confined within the carbon cage structure.

Coordination Chemistry and Organometallic Compounds

Coordination compounds involving helium remain unknown due to the element's inability to donate electron pairs for coordinate bond formation. The closed-shell 1s² configuration prevents hybridization or orbital overlap necessary for traditional chemical bonding. Computational studies indicate that hypothetical helium coordination complexes would exhibit negative binding energies, confirming thermodynamic instability. Organometallic chemistry involving helium does not exist, as the element cannot participate in σ-bonding, π-bonding, or coordinate bonding mechanisms essential for organometallic compound formation.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Helium demonstrates crustal abundance of approximately 0.008 ppm by weight, ranking among the rarest elements in Earth's solid crust. Atmospheric concentration reaches 5.24 ppm by volume, maintained through balance between α-decay production from radioactive elements and escape to space. Natural gas deposits provide the primary commercial source, with concentrations reaching 7% by volume in certain wells, particularly in regions with high uranium and thorium content. Helium concentrates in specific geological formations through α-particle capture from radioactive decay of uranium-238, thorium-232, and their decay products over geological time scales.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

Natural helium consists predominantly of helium-4 (⁴He, 99.999863% abundance) with trace amounts of helium-3 (³He, 0.000137% abundance). Helium-4 nuclei demonstrate exceptional stability with binding energy 28.296 MeV, identical to α-particles produced in radioactive decay processes. Helium-3 possesses nuclear spin I = ½ with magnetic moment μ = -2.127625 nuclear magnetons, making it valuable for neutron detection and magnetic resonance applications. Additional radioactive isotopes include helium-5 through helium-10, all exhibiting extremely short half-lives measured in microseconds or less. Nuclear cross-sections for thermal neutron absorption remain negligible for both stable isotopes.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Commercial helium production relies primarily on fractional distillation of natural gas streams containing significant helium concentrations. The process exploits helium's low boiling point relative to other gaseous components, utilizing cascade cooling systems reaching cryogenic temperatures. Initial gas processing removes carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and heavy hydrocarbons before cryogenic separation in distillation columns. Helium purification achieves 99.995% purity through multiple distillation stages, with nitrogen representing the primary impurity requiring removal. Global production capacity approximates 180 million standard cubic meters annually, with the United States providing approximately 75% of world supply from natural gas operations in Texas, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

Cryogenic applications consume approximately 32% of global helium production, primarily for cooling superconducting magnets in medical MRI scanners and nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometers. The element serves as pressurizing gas for rocket propulsion systems, including space launch vehicles where helium purges fuel lines and maintains tank pressurization. Deep-sea diving applications utilize helium-oxygen mixtures (heliox) and helium-nitrogen-oxygen mixtures (trimix) to prevent nitrogen narcosis and reduce breathing resistance at extreme depths. Leak detection systems employ helium's small atomic size and chemical inertness for identifying minute gas leaks in vacuum systems and pressurized equipment. Growing demand for quantum computing applications may increase helium consumption for dilution refrigerators operating at millikelvin temperatures.

Historical Development and Discovery

Helium discovery began with Pierre Janssen's spectroscopic observations during the 1868 solar eclipse, revealing a distinctive yellow spectral line at 587.49 nm in the Sun's chromosphere. Norman Lockyer and Edward Frankland proposed the existence of a new solar element, naming it helium from the Greek word "helios" meaning sun. William Ramsay achieved terrestrial isolation in 1895 by treating uranium-bearing mineral cleveite with mineral acids, collecting the evolved gas and identifying characteristic spectral lines. Simultaneously, Per Teodor Cleve and Nils Abraham Langlet independently isolated helium from similar uranium mineral sources. Industrial applications developed during World War I when helium replaced hydrogen in military airships, recognizing the element's non-flammable properties following hydrogen-related disasters.

Conclusion

Helium occupies a unique position in the periodic table as the first noble gas, exhibiting complete chemical inertness and exceptional physical properties including the lowest boiling point of all elements. Its significance extends beyond academic interest to critical applications in medical imaging, space exploration, and fundamental physics research. The element's scarcity and non-renewable nature on Earth necessitates careful resource management and recycling programs. Future research directions focus on helium recovery technologies, alternative cryogenic coolants, and expanded applications in quantum technologies requiring ultra-low temperature environments.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.