| Element | |

|---|---|

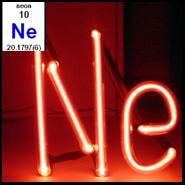

10NeNeon20.179762

8 |

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 10 |

| Atomic weight | 20.17976 amu |

| Element family | Nobel gases |

| Period | 2 |

| Group | 18 |

| Block | p-block |

| Discovery year | 1898 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

20Ne 90.51% 21Ne 0.27% 22Ne 9.22% |

20Ne (90.51%) 22Ne (9.22%) |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 0.0008999 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | -248.447 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Boiling | -246.1 °C |

Helium (He) -268.9 Tungsten (W) 5927 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| Oxidation states (less common) | (0) |

| First ionization potential | 21.564 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | -1.200 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Atomic radius | |

|---|---|

| Covalent radius | 0.67 Å |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 0.32 Francium (Fr) 2.6 | |

| Van der Waals radius | 1.54 Å |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 1.2 Francium (Fr) 3.48 | |

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8 |

| Electronic configuration | [He] 2s2 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 8 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

Neon (Ne): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

Neon (Ne) stands as the second noble gas element in the periodic table, possessing atomic number 10 and exhibiting exceptional chemical inertness. This monatomic gas demonstrates a unique electronic configuration of 1s22s22p6, representing the first complete octet configuration in the periodic table. Neon's physical properties include a melting point of 24.56 K, boiling point of 27.07 K, and density of 0.8999 g·L-1 at standard conditions. Despite ranking as the fifth most abundant element in the universe by mass, neon exhibits remarkable scarcity on Earth due to its high volatility and inability to form stable compounds under terrestrial conditions. The element finds primary applications in specialized lighting systems and cryogenic refrigeration, where its distinctive red-orange emission spectrum and superior thermodynamic properties prove essential for technological advancement.

Introduction

Neon occupies a pivotal position as the second member of Group 18 (VIIIA) in the modern periodic table, establishing the fundamental prototype for noble gas behavior in chemical systems. Located in Period 2, this element demonstrates the first complete manifestation of the octet rule, exhibiting an electronic structure that provides exceptional stability through filled 2s and 2p orbitals. The element's position between fluorine and sodium establishes critical periodic trends in ionization energy, atomic radius, and electronegativity that define second-period chemistry. Discovered through systematic fractional distillation of liquid air by William Ramsay and Morris Travers in 1898, neon's identification marked a crucial advancement in understanding atmospheric composition and noble gas chemistry. The distinctive bright red-orange emission spectrum immediately distinguished neon from other atmospheric constituents, providing the foundation for subsequent spectroscopic investigations and technological applications that continue to define modern gas discharge physics.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Neon's atomic structure centers on a nuclear composition containing 10 protons and typically 10 neutrons, yielding an atomic mass of 20.1797 u. The electronic configuration 1s22s22p6 represents the first complete shell closure beyond helium, establishing the archetypal noble gas electron arrangement. The atomic radius measures 38 pm (covalent), while the van der Waals radius extends to 154 pm, reflecting the element's pronounced electron cloud diffuseness. Effective nuclear charge calculations indicate a shielding constant of 2.85, resulting in Zeff values of 6.85 for 2s electrons and 4.45 for 2p electrons. First ionization energy reaches 2080.7 kJ·mol-1, representing one of the highest values in the periodic table and directly correlating with the exceptional stability of the complete 2p6 electron configuration. Second ionization energy escalates dramatically to 3952.3 kJ·mol-1, reflecting the extreme difficulty in removing electrons from the stable 1s22s22p5 configuration.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

Under standard conditions, neon manifests as a colorless, odorless monatomic gas exhibiting exceptional chemical inertness. The crystalline structure at low temperatures adopts a face-centered cubic lattice with space group Fm3̄m, characteristic of noble gas solids. Melting point occurs at 24.56 K (-248.59°C), accompanied by a heat of fusion of 0.335 kJ·mol-1. Boiling point reaches 27.07 K (-246.08°C) with heat of vaporization measuring 1.71 kJ·mol-1. Liquid neon demonstrates density of 1.207 g·cm-3 at the boiling point, while gaseous neon exhibits density of 0.8999 g·L-1 at 273.15 K and 101.325 kPa. Specific heat capacity of gaseous neon measures 1.030 kJ·kg-1·K-1 at constant pressure. The critical temperature reaches 44.40 K with critical pressure of 2.76 MPa, defining the phase boundary limits for neon's thermodynamic behavior. Triple point coordinates establish at 24.5561 K and 43.37 kPa, serving as a fundamental reference point in the International Temperature Scale of 1990.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

Neon's electronic configuration 1s22s22p6 establishes complete orbital filling in both s and p subshells, creating extraordinary chemical stability through optimal electron-electron repulsion minimization and nuclear-electron attraction maximization. The absence of available valence orbitals at reasonable energies precludes conventional covalent bond formation, relegating neon's chemical behavior to weak intermolecular interactions dominated by London dispersion forces. Polarizability measures 2.67 × 10-31 m3, indicating minimal electron cloud deformation under external electric fields. No stable neutral compounds exist under ambient conditions, though theoretical calculations suggest possible compound formation under extreme pressures exceeding 100 GPa. Matrix isolation techniques have enabled detection of metastable species such as NeH+ and HeNe+ through mass spectrometric analysis, demonstrating limited ionization-driven chemical reactivity. Bond dissociation energies for these ionic species remain exceptionally low, typically below 10 kJ·mol-1, confirming the fundamental inertness of neon's electronic structure.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Electronegativity values vary significantly depending on the scale employed, with Pauling electronegativity remaining undefined due to the absence of stable chemical bonds. Allen electronegativity reaches 4.787, positioning neon as the most electronegative element according to this atomic energy-based scale. Successive ionization energies demonstrate dramatic increases: first ionization at 2080.7 kJ·mol-1, second at 3952.3 kJ·mol-1, and third at 6122 kJ·mol-1. Electron affinity measurements indicate slightly negative values around -116 kJ·mol-1, confirming the instability of Ne- anions under normal conditions. Standard electrode potentials remain undefined for conventional aqueous systems due to neon's chemical inertness. Thermodynamic stability manifests through negative standard formation enthalpies for hypothetical compounds, with theoretical calculations predicting endothermic formation energies exceeding 500 kJ·mol-1 for most potential neon-containing species. Heat capacity ratios (γ = Cp/Cv) equal 1.667 for monatomic neon gas, reflecting ideal gas behavior with three translational degrees of freedom.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

Neon's extreme chemical inertness severely limits compound formation under conventional conditions, with no thermodynamically stable binary compounds documented in standard chemical literature. Theoretical investigations predict potential oxide formation (NeO) under pressures exceeding 100 GPa, though experimental verification remains absent. Halide formation appears thermodynamically unfavorable across all oxidation states, with calculated formation enthalpies indicating extreme endothermic processes. Hydride species (NeH) demonstrate similar instability, existing only as transient intermediates in plasma discharge conditions or high-energy radiation environments. Matrix isolation studies have identified weak adducts such as Ne·HF and Ne·N2 at temperatures below 10 K, characterized by binding energies typically below 1 kJ·mol-1. Clathrate hydrate formation occurs under extreme pressure conditions (350-480 MPa) and low temperatures (-30°C), producing ice structures incorporating neon atoms within molecular cavities. These clathrate systems demonstrate reversible formation with neon atoms remaining physically trapped rather than chemically bonded, enabling complete gas recovery through vacuum extraction.

Coordination Chemistry and Organometallic Compounds

Coordination complex formation remains extremely limited due to neon's inability to donate electron density for coordinate bond formation. The sole documented coordination species involves Cr(CO)5Ne, exhibiting an exceptionally weak Ne-Cr interaction with bond dissociation energy below 5 kJ·mol-1. This complex forms exclusively under matrix isolation conditions at temperatures below 20 K, dissociating rapidly upon warming to ambient conditions. Computational studies suggest possible coordination with highly electrophilic metal centers under extreme conditions, though experimental verification remains challenging due to the prohibitive energy requirements for stable complex formation. Organometallic chemistry remains essentially nonexistent for neon, reflecting the element's complete inability to participate in carbon-metal bonding schemes. Theoretical calculations indicate that hypothetical organo-neon compounds would require formation energies exceeding 1000 kJ·mol-1, placing such species far beyond experimental accessibility under current technological limitations.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Neon exhibits remarkable cosmic abundance, ranking as the fifth most abundant element in the universe by mass with concentrations approaching 1 part in 750. Solar abundance reaches approximately 1 part in 600 by mass, reflecting primordial nucleosynthesis processes during early stellar evolution. Terrestrial abundance demonstrates dramatic depletion, with atmospheric concentrations measuring 18.2 ppm by volume (0.001818% mole fraction) and crustal abundance below 0.005 ppb by mass. This scarcity results from neon's high volatility and chemical inertness, preventing incorporation into mineral structures during planetary formation. Geochemical behavior remains dominated by physical partitioning rather than chemical fractionation, with preferential accumulation in gas phases during volcanic outgassing and hydrothermal processes. Deep mantle samples accessed through volcanic emissions show 20Ne enrichment, suggesting primordial neon retention within Earth's interior. Meteoritic samples demonstrate varying isotopic compositions correlating with formation environments, providing crucial constraints on early Solar System evolution and noble gas transport mechanisms.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

Natural neon consists of three stable isotopes: 20Ne (90.48% abundance), 21Ne (0.27% abundance), and 22Ne (9.25% abundance). 20Ne originates primarily from stellar nucleosynthesis through carbon-carbon fusion reactions occurring at temperatures exceeding 500 megakelvins in massive stellar cores. Nuclear spin states include I = 0 for 20Ne and 22Ne, while 21Ne exhibits I = 3/2 with nuclear magnetic moment μ = -0.661797 nuclear magnetons. Neutron capture cross-sections remain extremely small, with thermal values below 0.1 barns for all stable isotopes. 21Ne and 22Ne demonstrate nucleogenic production through neutron irradiation of 24Mg and 25Mg in uranium-rich geological environments, creating characteristic isotopic signatures in granite formations. Cosmogenic 21Ne production occurs through spallation reactions on aluminum, magnesium, and silicon targets, enabling determination of cosmic ray exposure ages for terrestrial and extraterrestrial samples. Radioactive isotopes range from 16Ne to 34Ne, with half-lives spanning from microseconds to minutes, providing valuable tracers for nuclear physics research and stellar nucleosynthesis studies.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Industrial neon production relies exclusively on cryogenic fractional distillation of liquefied air, exploiting differential volatility among atmospheric components. The process begins with air compression and cooling to approximately 78 K, enabling selective condensation of higher-boiling constituents while maintaining neon in the gas phase alongside helium and hydrogen. Primary separation occurs in rectification columns operating at pressures between 0.5-6.0 MPa, where careful temperature control enables neon concentration in overhead streams. Secondary purification involves selective adsorption on activated charcoal at liquid nitrogen temperatures, effectively removing residual helium through differential surface interactions. Hydrogen elimination proceeds through controlled oxidation to form water vapor, subsequently removed via condensation or desiccant treatment. Final purification achieves neon purity levels exceeding 99.995% through molecular sieve adsorption and specialized distillation techniques. Production efficiency requires processing approximately 88,000 pounds of atmospheric gas mixture to yield one pound of pure neon. Global production capacity approaches 500 metric tons annually, with major facilities concentrated in Ukraine, Russia, and China, reflecting regional steel production patterns that provide essential raw gas streams.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

Neon applications span diverse technological sectors, with lighting systems representing the predominant commercial use. Gas discharge tubes operating at 2-15 kilovolts produce neon's characteristic red-orange emission through electronic excitation and subsequent photon emission at wavelengths near 650 nm. Helium-neon laser systems utilize neon as the gain medium, generating coherent radiation at 632.8 nm with applications in precision measurement, holography, and optical alignment systems. Cryogenic refrigeration employs liquid neon as an intermediate coolant, providing refrigeration capacity approximately 40 times greater than liquid helium on a per-volume basis. Semiconductor manufacturing increasingly relies on high-purity neon for excimer laser systems essential in photolithography processes, particularly for advanced node production below 10 nm. Emerging applications include plasma display technology, where neon serves as a protective gas in discharge cells, and specialized analytical instrumentation requiring inert atmospheres. Future prospects encompass advanced laser development for quantum communication systems and potential space-based applications exploiting neon's unique thermodynamic properties. Economic considerations favor increased production diversification to reduce geopolitical supply vulnerabilities, particularly given recent disruptions affecting Ukrainian and Russian production facilities.

Historical Development and Discovery

Neon's discovery emerged from systematic investigations of atmospheric composition conducted by William Ramsay and Morris Travers at University College London during the late 19th century. Following successful isolations of argon (1894) and helium (1895), the research team pursued comprehensive analysis of residual atmospheric gases through sophisticated fractional distillation techniques. The discovery process commenced in May 1898 with careful liquefaction of air samples, followed by controlled warming to separate components based on differential volatility. Initial separation yielded krypton in early June, followed by identification of neon through spectroscopic analysis revealing brilliant red emission lines under electrical discharge conditions. Travers documented the moment: "the blaze of crimson light from the tube told its own story and was a sight to dwell upon and never forget." The element name derived from Greek "neos" meaning new, suggested by Ramsay's son. Subsequent purification enabled determination of atomic weight and spectroscopic properties, establishing neon's position in the emerging periodic classification system. Early applications remained limited until Georges Claude developed practical neon lighting systems in 1910, culminating in widespread adoption for advertising signage by 1920. The element played crucial roles in atomic theory development, with J.J. Thomson's 1913 mass spectrometric studies of neon providing first experimental evidence for stable isotopes, fundamentally advancing understanding of atomic structure and nuclear composition.

Conclusion

Neon's exceptional position in the periodic table stems from its unique combination of complete electronic shell closure and distinctive physical properties that establish fundamental principles governing noble gas behavior. The element's extreme chemical inertness, arising from optimal electronic configuration stability, demonstrates the profound influence of quantum mechanical principles on macroscopic chemical phenomena. Despite terrestrial scarcity, neon's technological significance continues expanding through specialized applications in advanced lighting systems, precision laser technology, and cryogenic engineering. Future research directions encompass exploration of extreme pressure chemistry for potential compound synthesis and development of novel applications exploiting neon's unparalleled electronic and thermodynamic characteristics. The element's fundamental importance in understanding periodic trends, stellar nucleosynthesis, and atmospheric evolution ensures continued scientific relevance across multiple disciplines within modern chemistry and physics.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.