| Element | |

|---|---|

43TcTechnetium98.90632

8 18 13 2 |

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 43 |

| Atomic weight | 98.9063 amu |

| Element family | Transition metals |

| Period | 5 |

| Group | 2 |

| Block | s-block |

| Discovery year | 1937 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

| None |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 11.5 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | 2200 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Boiling | 5030 °C |

Helium (He) -268.9 Tungsten (W) 5927 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| Oxidation states (less common) | +4, +7 (-1, +1, +2, +3, +5, +6) |

| First ionization potential | 7.276 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | 0.550 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Electronegativity | 1.9 |

Cesium (Cs) 0.79 Atomic fluorine (F) 3.98 | |

| Atomic radius | |

|---|---|

| Covalent radius | 1.28 Å |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 0.32 Francium (Fr) 2.6 | |

| Van der Waals radius | 2.05 Å |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 1.2 Francium (Fr) 3.48 | |

| Metallic radius | 1.36 Å |

Beryllium (Be) 1.12 Cesium (Cs) 2.65 | |

| Compounds | ||

|---|---|---|

| Formula | Name | Oxidation state |

| TcCl3 | Technetium trichloride | +3 |

| TcBr4 | Technetium(IV) bromide | +4 |

| TcCl4 | Technetium(IV) chloride | +4 |

| TcO2 | Technetium(IV) oxide | +4 |

| NaTcO3 | Sodium technetate(V) | +5 |

| TcF5 | Technetium pentafluoride | +5 |

| TcF6 | Technetium hexafluoride | +6 |

| HTcO4 | Pertechnetic acid | +7 |

| NaTcO4 | Sodium pertechnetate | +7 |

| Tc2O7 | Technetium(VII) oxide | +7 |

| TcO3F | Pertechnetyl fluoride | +7 |

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 13, 2 |

| Electronic configuration | [Kr] 4d5 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 7 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

Technetium (Tc): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

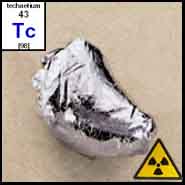

Technetium, with atomic number 43 and symbol Tc, represents a unique position in the periodic table as the lightest element whose isotopes are all radioactive. Located in Group 7 between molybdenum and ruthenium, technetium is a silvery-gray crystalline transition metal with properties intermediate between manganese and rhenium. The element holds historical significance as the first artificially produced element, discovered in 1937 by Emilio Segrè and Carlo Perrier through bombardment of molybdenum targets. All technetium isotopes are radioactive with half-lives ranging from microseconds to millions of years, precluding significant natural occurrence on Earth. Despite its radioactive nature, technetium has found important applications in nuclear medicine, particularly as technetium-99m for diagnostic imaging procedures.

Introduction

Technetium occupies a distinctive position in modern chemistry as the first element to be artificially synthesized, earning its name from the Greek word technetos meaning "artificial." With atomic number 43, technetium fills the gap in the periodic table between molybdenum (42) and ruthenium (44), exhibiting chemical properties characteristic of Group 7 transition metals. The element's electronic structure, [Kr]4d55s2, places it among the d-block elements where partially filled d orbitals contribute to its metallic bonding and chemical reactivity. The complete absence of stable isotopes makes technetium fundamentally different from its neighboring elements, with profound implications for its natural abundance and technological applications. Understanding technetium's properties provides insights into nuclear physics, radiochemistry, and the behavior of artificial elements in chemical systems.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Technetium exhibits atomic number Z = 43 with an electronic configuration of [Kr]4d55s2, representing a half-filled d subshell configuration that contributes to its stability within the transition metal series. The atomic radius of technetium measures approximately 136 pm, positioned between molybdenum (139 pm) and ruthenium (134 pm), demonstrating the expected lanthanide contraction effect across the second transition series. The effective nuclear charge experienced by valence electrons increases progressively from molybdenum to ruthenium, with technetium showing intermediate behavior. Ionic radii vary according to oxidation state, with Tc4+ exhibiting a radius of 64.5 pm and Tc7+ showing 56 pm, reflecting the increased electrostatic attraction in higher oxidation states. The element's covalent radius measures 127 pm, consistent with its position in the periodic table and metallic bonding characteristics.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

Technetium appears as a lustrous silvery-gray metal with hexagonal close-packed crystal structure at room temperature, exhibiting metallic bonding typical of transition metals. The element demonstrates a melting point of 2157°C and boiling point of 4265°C, values that reflect strong metallic bonding due to the delocalized d electrons. Heat of fusion measures 33.29 kJ/mol while the heat of vaporization reaches 585.2 kJ/mol, indicating substantial energy requirements for phase transitions. Density at room temperature equals 11.50 g/cm³, placing technetium among the moderately dense transition metals. The specific heat capacity measures 0.210 J/g·K, with thermal conductivity of 50.6 W/m·K demonstrating moderate thermal transport properties. Technetium exhibits paramagnetic behavior with a magnetic susceptibility of +2.70 × 10-4 cm³/mol, consistent with unpaired d electrons in its electronic structure.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

The d5 configuration of technetium enables multiple oxidation states ranging from -3 to +7, with +4, +5, and +7 being most commonly observed in chemical compounds. The partially filled d orbitals participate in both σ and π bonding interactions, allowing formation of complex coordination geometries and organometallic compounds. In aqueous solution, technetium readily adopts the +7 oxidation state as the pertechnetate ion TcO4-, which exhibits tetrahedral geometry and remarkable stability. Lower oxidation states demonstrate increased tendency toward metal-metal bonding, particularly in the +2 and +3 states where dimeric and cluster compounds form through direct Tc-Tc bonds. Bond enthalpies for Tc-O bonds measure approximately 548 kJ/mol, while Tc-Cl bonds exhibit energies around 339 kJ/mol, reflecting the element's strong affinity for oxygen-containing ligands.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Technetium exhibits an electronegativity of 1.9 on the Pauling scale, positioned between molybdenum (2.16) and ruthenium (2.2), reflecting its intermediate metallic character within Group 7. The first ionization energy measures 702 kJ/mol, considerably lower than its lighter congener manganese (717 kJ/mol) but higher than heavier rhenium (760 kJ/mol). Successive ionization energies follow expected trends with the second ionization energy at 1472 kJ/mol and third at 2850 kJ/mol, demonstrating the progressive difficulty of electron removal from the d5 configuration. Standard reduction potentials vary significantly with pH and ligand environment, with the TcO4-/TcO2 couple showing E° = +0.738 V in acidic solution. The Tc4+/Tc potential measures -0.4 V, indicating the stability of higher oxidation states in aqueous media.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

Technetium forms a comprehensive range of binary oxides including TcO2, Tc2O7, and the unstable TcO3 identified only in gas phase studies. Technetium dioxide adopts a rutile structure with Tc4+ ions in octahedral coordination, exhibiting amphoteric behavior in acidic and basic solutions. The heptoxide Tc2O7 represents the highest oxidation state oxide, forming yellow crystals that readily dissolve in water to produce pertechnetate solutions. Halide compounds include TcF6, TcF5, TcCl4, and TcBr4, with the hexafluoride being particularly stable due to the high electronegativity of fluorine. Sulfide formation yields TcS2 with a pyrite-type structure, while the nitride TcN adopts a face-centered cubic lattice. Ternary compounds include perovskite-structured Ba2TcO6 and spinel-type Li2TcO3, demonstrating technetium's ability to incorporate into complex oxide frameworks.

Coordination Chemistry and Organometallic Compounds

Technetium exhibits extensive coordination chemistry with coordination numbers ranging from 4 to 9, though octahedral geometry predominates in most complexes. Ligand field effects significantly influence the stability and properties of technetium coordination compounds, with strong field ligands such as cyanide and carbonyl promoting lower oxidation states. The complex [Tc(CO)6]+ represents a stable organometallic species with technetium in the +1 oxidation state, demonstrating significant π-backbonding between metal d orbitals and carbonyl π* orbitals. Phosphine complexes such as [TcCl4(PPh3)2] exhibit square planar geometry around Tc4+ centers, while nitrogen donor ligands form octahedral complexes like [Tc(NH3)6]3+. Chelating ligands including ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) form thermodynamically stable complexes exploited in radiopharmaceutical applications. Metal-metal bonded species such as [Tc2Cl8]2- demonstrate the tendency of lower oxidation state technetium to form cluster compounds.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Technetium occurs naturally in Earth's crust at extremely low concentrations of approximately 0.003 parts per trillion (3 × 10-12 g/g), making it one of the rarest naturally occurring elements. This scarcity results from the radioactive decay of all technetium isotopes over geological time scales, as the longest-lived isotopes 97Tc and 98Tc possess half-lives of only 4.2 million years. Natural technetium arises primarily through spontaneous fission of uranium-238 in uranium ores, where fission yields produce trace quantities of 99Tc. A kilogram of pitchblende typically contains approximately 1 nanogram of technetium, equivalent to roughly 1013 atoms. Additional sources include neutron capture processes in molybdenum ores within uranium-rich geological formations, though this mechanism contributes negligibly to total technetium abundance. The element's geochemical behavior resembles that of rhenium, with preference for sulfide-rich environments and moderate mobility in oxidizing aqueous solutions as pertechnetate ion.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

All known technetium isotopes are radioactive, spanning mass numbers from 86 to 122 with no stable nuclear configurations. The most stable isotopes are 97Tc and 98Tc, both possessing half-lives of 4.21 ± 0.16 million years and 4.2 ± 0.3 million years respectively, with overlapping uncertainty intervals preventing definitive assignment of the longest-lived isotope. 99Tc follows as the third most stable isotope with a half-life of 211,100 years, undergoing beta decay to stable 99Ru with decay energy of 294 keV. The metastable isomer 99mTc exhibits a half-life of 6.01 hours, decaying via internal conversion and gamma emission to 99Tc, making it invaluable for medical imaging applications. Nuclear spin values vary among isotopes, with 99Tc possessing I = 9/2 and magnetic moment μ = +5.6847 nuclear magnetons. Cross-sections for thermal neutron absorption range from 20 barns for 99Tc to over 1000 barns for some shorter-lived isotopes, influencing their behavior in nuclear reactor environments and neutron activation processes.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Industrial production of technetium relies primarily on extraction from spent nuclear fuel where 99Tc accumulates as a fission product with yields of approximately 6% per fission event. Reprocessing facilities employ solvent extraction techniques using tributyl phosphate (TBP) in kerosene to separate pertechnetate from other fission products, taking advantage of technetium's unique extraction behavior. The PUREX process initially concentrates technetium in high-level waste streams, requiring subsequent separation using anion exchange resins that selectively retain TcO4- ions. Alternative production routes include neutron bombardment of molybdenum-98 targets in nuclear reactors, producing 99Mo which decays to 99mTc for medical applications. Purification involves successive precipitation as technetium sulfide followed by oxidative dissolution and ion exchange chromatography to achieve nuclear medicine grade purity exceeding 99.9%. Annual global production reaches approximately 20 kg of 99Tc from reprocessing operations, with additional quantities of 99mTc produced on-demand for medical procedures.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

The primary technological application of technetium lies in nuclear medicine, where 99mTc serves as the most widely used radioisotope for diagnostic imaging procedures. The optimal nuclear properties of 99mTc, including 140 keV gamma radiation and 6-hour half-life, enable high-quality medical imaging with minimal radiation exposure to patients. Radiopharmaceuticals incorporating 99mTc complexes target specific organs and tissues, facilitating diagnosis of cardiac conditions, bone disorders, and malignancies through single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). Industrial applications exploit technetium's exceptional corrosion inhibition properties, where pertechnetate additions at concentrations as low as 10-5 M provide superior protection for steel in aqueous environments compared to conventional inhibitors. Research applications utilize technetium as a chemical analog for rhenium in catalyst development and as a tracer for environmental studies. Future prospects include development of technetium-based radiopharmaceuticals with enhanced targeting specificity and investigation of technetium compounds for potential use in advanced nuclear reactor systems where its neutron absorption properties may prove beneficial.

Historical Development and Discovery

The discovery of technetium unfolded through multiple historical attempts spanning several decades, beginning with erroneous claims by German chemists Walter Noddack, Otto Berg, and Ida Tacke in 1925. This research group reported detecting element 43 in columbite samples through X-ray emission spectroscopy and proposed the name "masurium" after the Masuria region. However, subsequent investigations failed to reproduce their results, and modern calculations demonstrate that natural technetium concentrations in available ores would be insufficient for detection using their analytical methods. The definitive discovery occurred in 1937 when Emilio Segrè and Carlo Perrier at the University of Palermo analyzed molybdenum targets that had been bombarded with deuterons at the Lawrence Berkeley cyclotron. Chemical separation and characterization studies confirmed the presence of element 43, representing the first artificially produced element in human history. Initial naming proposals included "panormium" after Palermo's Latin designation, but the researchers ultimately chose "technetium" from the Greek word technetos meaning artificial. This discovery validated theoretical predictions about the instability of element 43 and demonstrated the possibility of creating new elements through nuclear bombardment techniques, establishing precedents for subsequent transuranium element discoveries.

Conclusion

Technetium represents a unique intersection of nuclear physics and chemistry, serving as the first artificially produced element and the lightest completely radioactive element. Its position in Group 7 of the periodic table provides valuable insights into transition metal chemistry, while its radioactive nature offers important applications in nuclear medicine and industrial radiochemistry. The element's discovery marked a pivotal moment in nuclear science, demonstrating humanity's capability to create new elements and expanding our understanding of nuclear stability. Future research directions will likely focus on developing more targeted radiopharmaceuticals, exploring technetium's role in advanced nuclear technologies, and investigating fundamental aspects of its chemical behavior in complex environments.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.