| Element | |

|---|---|

100FmFermium257.09512

8 18 32 30 8 2 |

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 100 |

| Atomic weight | 257.0951 amu |

| Element family | Actinoids |

| Period | 7 |

| Group | 2 |

| Block | s-block |

| Discovery year | 1952 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

| None |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 9.7 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | 1527 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| Oxidation states (less common) | +3 (+2) |

| First ionization potential | 6.498 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | 0.350 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Electronegativity | 1.3 |

Cesium (Cs) 0.79 Atomic fluorine (F) 3.98 | |

| Atomic radius |

|---|

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 30, 8, 2 |

| Electronic configuration | [Rn] 5f12 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 14 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

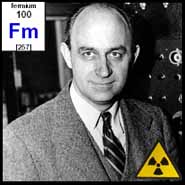

Fermium (Fm): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

Fermium (Fm, atomic number 100) represents a synthetic actinide element that occupies a unique position as the heaviest element synthesizable by neutron bombardment of lighter elements. Discovered in 1952 in the debris of the first hydrogen bomb explosion, fermium exhibits characteristic actinide chemistry with predominant +3 oxidation states and limited nuclear stability. The element's most stable isotope, 257Fm, possesses a half-life of 100.5 days, while other isotopes demonstrate significantly shorter decay periods. Fermium's chemical behavior manifests through enhanced complex formation relative to preceding actinides, attributed to increased effective nuclear charge. Current applications remain restricted to fundamental nuclear research due to production limitations and radioactive decay constraints.

Introduction

Fermium occupies atomic number 100 in the periodic table, representing the terminal element accessible through neutron capture synthesis methods. This synthetic actinide demonstrates fundamental importance in understanding superheavy element chemistry and nuclear physics principles. The element's electronic configuration [Rn]5f127s2 places it within the actinide series, exhibiting characteristic f-block properties with enhanced nuclear instability typical of transuranium elements. Named after Enrico Fermi, the pioneer of controlled nuclear reactions, fermium's discovery marked a significant milestone in superheavy element research. The element's position beyond the natural occurrence boundary necessitates artificial synthesis, limiting availability to specialized research facilities equipped with high-flux neutron sources or particle accelerators.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Fermium possesses atomic number 100 with electronic configuration [Rn]5f127s2, placing twelve electrons in the 5f subshell. The atomic radius has been estimated at approximately 1.70 Å based on theoretical calculations and comparison with neighboring actinides. Ionic radius for Fm3+ measures approximately 0.85 Å, reflecting the lanthanide contraction effect within the actinide series. The effective nuclear charge experienced by valence electrons increases significantly compared to lighter actinides, contributing to enhanced bonding characteristics and complex stability. Spectroscopic studies reveal energy level structures consistent with 5f12 configuration, though comprehensive atomic spectroscopy remains limited by sample availability and short half-lives.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

Fermium metal has not been isolated in bulk quantities, preventing direct measurement of macroscopic physical properties. Theoretical predictions suggest a face-centered cubic crystal structure typical of heavy actinides, with estimated density of approximately 9.7 g/cm³. The melting point is projected to be around 1800 K based on trends within the actinide series. Sublimation enthalpy measurements using fermium-ytterbium alloys yielded values of 142 ± 42 kJ/mol at 298 K. Magnetic susceptibility studies indicate paramagnetic behavior consistent with unpaired 5f electrons. The element exhibits metallic character in theoretical models, though experimental verification remains challenging due to sample limitations and radioactive decay.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

Fermium's chemical behavior demonstrates characteristic actinide properties with predominant +3 oxidation state stability. The 5f12 electronic configuration provides twelve unpaired electrons in aqueous solution, contributing to paramagnetic properties and specific spectroscopic signatures. The +2 oxidation state proves accessible under reducing conditions, with electrode potential Fm3+/Fm2+ estimated at -1.15 V versus standard hydrogen electrode. This reduction potential compares favorably with ytterbium(III)/(II), indicating moderate stability of the divalent state. Bonding in fermium complexes exhibits predominantly ionic character, with increased covalency compared to lighter actinides due to enhanced effective nuclear charge and contracted ionic radius.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Electrochemical studies reveal Fm3+/Fm0 standard reduction potential of -2.37 V, establishing fermium as highly electropositive. The Fm3+ ion exhibits hydration number of 16.9 in aqueous solution, with acid dissociation constant of 1.6 × 10-4 (pKa = 3.8). These values reflect enhanced charge density compared to preceding actinides, resulting in stronger metal-ligand interactions. Successive ionization energies follow predicted trends for actinides, with first ionization energy estimated at 627 kJ/mol. The enhanced effective nuclear charge contributes to contracted orbital radii and increased binding energies throughout the electron configuration.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

Fermium compounds remain limited to solution chemistry due to microscopic sample sizes and radioactive constraints. Fermium(II) chloride (FmCl2) has been identified through coprecipitation studies with samarium(II) chloride, representing the only characterized solid binary compound. Oxide formation likely follows actinide trends, suggesting stable Fm2O3 stoichiometry under oxidizing conditions. Halide complexes demonstrate enhanced stability relative to einsteinium and californium analogs, attributed to increased effective nuclear charge effects. Hydrolysis products include hydroxide species at elevated pH, with precipitation occurring above pH 3.8 based on acid dissociation measurements.

Coordination Chemistry and Complex Formation

Fermium(III) forms stable complexes with hard donor ligands containing oxygen and nitrogen atoms. Complexation with α-hydroxyisobutyrate demonstrates enhanced stability compared to lighter actinides, facilitating chromatographic separation protocols. Chloride and nitrate anionic complexes exhibit increased formation constants relative to californium and einsteinium analogs. The coordination number typically ranges from 8 to 9 in aqueous solution, consistent with large ionic radius requirements. Organic chelating agents such as EDTA and DTPA form exceptionally stable complexes, exploiting the high charge density of Fm3+. These coordination properties prove essential for separation and purification procedures in radiochemical processing.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Fermium does not occur naturally in Earth's crust due to the absence of stable isotopes and extremely short half-lives of all known nuclides. Primordial fermium, if present during Earth's formation, has completely decayed over geological timescales. The element briefly existed in the natural nuclear reactor at Oklo, Gabon, approximately 2 billion years ago through neutron capture processes, but no longer persists. Terrestrial fermium production occurs exclusively through artificial synthesis in nuclear reactors, particle accelerators, or nuclear weapons testing. Atmospheric detection following nuclear tests provides the only environmental occurrence, typically at femtogram to picogram levels dispersed in fallout debris.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

Twenty fermium isotopes are characterized with mass numbers ranging from 241 to 260. The most stable isotope, 257Fm, exhibits a half-life of 100.5 days through α-decay to 253Cf. Other significant isotopes include 255Fm (t½ = 20.07 hours), 254Fm (t½ = 3.2 hours), and 253Fm (t½ = 3.0 days). Isotopes heavier than 257Fm undergo spontaneous fission with microsecond to millisecond half-lives, creating the "fermium gap" that limits superheavy element synthesis via neutron capture. Nuclear properties follow predicted trends for actinides, with α-decay predominating for lighter isotopes and spontaneous fission becoming significant for heavier masses. Cross-sections for neutron capture reactions decrease dramatically with increasing mass number, contributing to synthesis limitations.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Fermium production relies primarily on neutron bombardment of lighter actinides in high-flux research reactors. The High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory serves as the primary source, producing picogram quantities through months-long irradiation campaigns. Target materials consist of curium or berkelium isotopes, with successive neutron captures leading to fermium formation. Production yields decrease exponentially with atomic number, limiting 257Fm availability to subnanogram quantities annually. Nuclear weapons testing historically provided larger amounts, with the 1969 Hutch test yielding 4.0 pg of 257Fm from 10 kg of debris, though recovery efficiency remained extremely low at 10-7 of total production.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

Current fermium applications focus exclusively on fundamental nuclear physics and chemistry research. Studies of superheavy element properties utilize fermium as a benchmark for theoretical model validation and spectroscopic technique development. Nuclear structure investigations employ fermium isotopes to explore shell effects and decay mechanisms near the proposed "island of stability." Potential future applications include neutron source development for specialized research and medical isotope production, though practical implementation requires significant advances in production efficiency. Enhanced synthesis methods through improved reactor designs or novel nuclear reactions may expand availability for applied research programs.

Historical Development and Discovery

The discovery of fermium emerged from the Manhattan Project's hydrogen bomb development program in the early 1950s. Initial detection occurred in debris analysis from the "Ivy Mike" thermonuclear test on November 1, 1952, at Enewetak Atoll. Albert Ghiorso and colleagues at the University of California Berkeley identified isotope 255Fm through its characteristic 7.1 MeV α-particle emissions and 20-hour half-life. The discovery remained classified until 1955 due to Cold War security concerns, despite independent synthesis by Swedish researchers in 1954 using ion bombardment techniques. Element naming honored Enrico Fermi, recognizing his contributions to nuclear physics and reactor development. Systematic studies began following declassification, establishing fermium's position as the heaviest neutron-capture synthesizable element and launching superheavy element research programs.

Conclusion

Fermium occupies a pivotal position in the periodic table as the terminal element accessible through neutron bombardment synthesis, marking the practical limit of bulk element production. Its unique nuclear properties and chemical behavior provide fundamental insights into actinide chemistry and superheavy element physics. The element's enhanced complex stability and distinctive electrochemical properties reflect increased effective nuclear charge effects characteristic of the heaviest actinides. While current applications remain confined to basic research due to synthesis limitations and radioactive instability, fermium continues to serve as a crucial benchmark for theoretical model development and experimental technique advancement in nuclear science.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.