| Element | |

|---|---|

61PmPromethium146.91512

8 18 23 8 2 |

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 61 |

| Atomic weight | 146.9151 amu |

| Element family | N/A |

| Period | 6 |

| Group | 2 |

| Block | s-block |

| Discovery year | 1945 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

| None |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 7.26 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | 931 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Boiling | 2730 °C |

Helium (He) -268.9 Tungsten (W) 5927 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| Oxidation states (less common) | +3 (+2) |

| First ionization potential | 5.597 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | 0.129 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Electronegativity | 1.13 |

Cesium (Cs) 0.79 Atomic fluorine (F) 3.98 | |

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 23, 8, 2 |

| Electronic configuration | [Xe] 4f5 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 7 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

Promethium (Pm): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

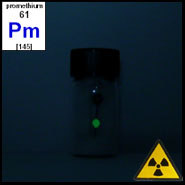

Promethium (Pm) is a synthetic radioactive lanthanide element with atomic number 61, representing one of only two elements in the first 82 positions of the periodic table that possess no stable isotopes. This rare earth metal exhibits typical trivalent lanthanide behavior, forming predominantly Pm³⁺ compounds characterized by pink to lavender coloration. All promethium isotopes are radioactive, with promethium-145 exhibiting the longest half-life of 17.7 years via electron capture. The element demonstrates unique nuclear instability due to unfavorable nuclear configurations predicted by the Mattauch isobar rule. Promethium displays characteristic lanthanide contraction effects, double hexagonal close-packed crystal structure, and forms various halides, oxides, and coordination complexes. Industrial applications center on promethium-147, utilized in luminous paints, atomic batteries, and thickness gauging devices due to its beta-decay properties and manageable radiation penetration characteristics.

Introduction

Promethium occupies position 61 in the periodic table as the penultimate member of the first lanthanide series, situated between neodymium and samarium. This element represents a remarkable case of nuclear instability within the rare earth metals, being one of only two elements among the first 82 that lacks stable or long-lived isotopes. The absence of stable promethium isotopes results from nuclear configuration constraints described by the Mattauch isobar rule, which prohibits stable isobars with the same mass number in adjacent elements. Promethium's electron configuration [Xe] 4f⁵ 6s² places it firmly within the lanthanide series, exhibiting characteristic f-block electronic behavior and chemical properties intermediate between its neighbors neodymium and samarium. The element was first isolated and characterized in 1945 from uranium fission products at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, concluding a decades-long search for the missing element 61 predicted by Moseley's systematic studies of atomic numbers in 1914. Named after Prometheus, the Titan who stole fire from the gods in Greek mythology, promethium symbolizes both the promise and potential hazards of nuclear technology.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Promethium exhibits atomic number 61 with a ground-state electron configuration of [Xe] 4f⁵ 6s², placing five electrons in the 4f subshell and two in the 6s orbital. The atomic radius of promethium measures approximately 183 pm, representing the second largest value among all lanthanides and constituting a notable exception to the general lanthanide contraction trend. This anomalous behavior arises from the half-filled 4f⁵ configuration, which provides additional electronic stability and results in reduced effective nuclear charge experienced by the outer electrons. The ionic radius of Pm³⁺ measures 97.3 pm in octahedral coordination, intermediate between Nd³⁺ (98.3 pm) and Sm³⁺ (95.8 pm). Successive ionization energies follow the expected lanthanide pattern: first ionization energy 540 kJ/mol, second ionization energy 1050 kJ/mol, and third ionization energy 2150 kJ/mol, reflecting the removal of 6s and 4f electrons. The effective nuclear charge experienced by valence electrons is approximately 2.85, accounting for significant shielding by inner electron shells.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

Promethium metal exhibits a silvery-white metallic appearance with typical lanthanide characteristics. The element crystallizes in two distinct polymorphs: a low-temperature α-form with double hexagonal close-packed (dhcp) structure and space group P63/mmc, and a high-temperature β-form with body-centered cubic (bcc) structure and space group Im3m. The α → β phase transition occurs at 890°C, accompanied by a decrease in density from 7.26 g/cm³ to 6.99 g/cm³. The dhcp α-phase exhibits lattice parameters a = 365 pm, c = 1165 pm with c/a ratio of 3.19, while the bcc β-phase shows a = 410 pm. The melting point of promethium is 1042°C, and the estimated boiling point is 3000°C based on periodic trends. Heat of fusion measures 7.13 kJ/mol, while heat of vaporization is estimated at 289 kJ/mol. Specific heat capacity at 25°C is 27.20 J/(mol·K), consistent with Dulong-Petit law predictions. The element displays Vickers hardness of 63 kg/mm², indicating typical lanthanide mechanical properties. Electrical resistivity at room temperature is approximately 0.75 μΩ·m, reflecting metallic conduction behavior.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

The electronic configuration of promethium governs its chemical behavior, with the 4f⁵ configuration providing moderate stability through half-filled subshell effects. Promethium readily adopts the +3 oxidation state through loss of two 6s electrons and one 4f electron, forming the Pm³⁺ ion with [Xe] 4f⁴ electron configuration. The resulting Pm³⁺ ion exhibits pink coloration due to f-f electronic transitions, with absorption maxima in the visible spectrum consistent with other trivalent lanthanides. The ground state term symbol for Pm³⁺ is ⁵I₄, arising from Russell-Saunders coupling of four unpaired f electrons. Promethium can also form the +2 oxidation state under reducing conditions, analogous to samarium and europium, with thermodynamic calculations suggesting stability of PmCl₂ similar to SmCl₂. Covalent bonding contributions in promethium compounds remain minimal due to poor overlap between f orbitals and ligand orbitals, resulting in predominantly ionic character. Coordination numbers typically range from 8 to 12 in solid compounds, reflecting the large ionic radius and electrostatic bonding preferences.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Promethium exhibits electronegativity values of 1.13 on the Pauling scale and 1.07 on the Allred-Rochow scale, consistent with other lanthanides and indicating electropositive character. The standard electrode potential for the Pm³⁺/Pm couple is -2.42 V versus standard hydrogen electrode, similar to neighboring lanthanides and confirming the element's strong reducing character. Electron affinity is estimated at 50 kJ/mol based on periodic trends, indicating minimal tendency to form anions. The small separation between successive ionization energies (540 kJ/mol for first, 1050 kJ/mol for second) facilitates formation of Pm²⁺ ions under appropriate conditions. Hydration enthalpy of Pm³⁺ measures -3560 kJ/mol, intermediate between Nd³⁺ (-3590 kJ/mol) and Sm³⁺ (-3540 kJ/mol), reflecting the ionic radius trends. Standard enthalpy of formation of Pm³⁺(aq) is -665 kJ/mol, while standard entropy is -226 J/(mol·K). These thermodynamic parameters indicate moderate stability of aqueous Pm³⁺ ions and typical lanthanide solution behavior. Redox chemistry involves primarily the Pm³⁺/Pm²⁺ couple, with standard reduction potential estimated at -1.55 V.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

Promethium oxide (Pm₂O₃) represents the most thermodynamically stable binary compound, formed by direct oxidation of the metal or thermal decomposition of promethium salts. The oxide exhibits three distinct polymorphs: a disordered cubic form (Ia3, a = 1099 pm) stable at moderate temperatures, a monoclinic form (C2/m) stable at intermediate temperatures, and a hexagonal form (P3m1) stable at high temperatures. The cubic → monoclinic → hexagonal transitions occur at approximately 600°C and 1750°C respectively, with densities of 6.77, 7.40, and 7.53 g/cm³ for the respective phases. Promethium halides demonstrate typical lanthanide behavior with decreasing lattice energies following the order F⁻ > Cl⁻ > Br⁻ > I⁻. Promethium trifluoride (PmF₃) exhibits purple-pink coloration, hexagonal crystal structure (P3c1), and melting point of 1338°C. The trichloride (PmCl₃) displays lavender color, hexagonal structure (P6₃/mc), and melts at 655°C. Promethium tribromide (PmBr₃) and triiodide (PmI₃) crystallize in orthorhombic (Cmcm) and rhombohedral (R3) structures respectively, with melting points of 624°C and 695°C. Binary sulfides, nitrides, and phosphides follow typical lanthanide stoichiometries, though detailed structural characterization remains limited due to material scarcity.

Coordination Chemistry and Organometallic Compounds

Promethium forms extensive coordination complexes with various ligands, exhibiting typical lanthanide coordination behavior with high coordination numbers and predominantly electrostatic bonding. The first characterized promethium coordination complex involved neutral PyDGA (N,N-diethyl-2-pyridine-6-carboxamide) ligands in aqueous solution, demonstrating coordination numbers of 8-9 with bidentate ligand arrangements. Promethium nitrate (Pm(NO₃)₃) forms pink crystals isomorphous with neodymium nitrate, indicating similar coordination environments. In aqueous solution, Pm³⁺ typically coordinates 8-9 water molecules in the first coordination sphere with additional waters in outer spheres. Chelating ligands such as EDTA, DTPA, and related aminopolycarboxylates form stable complexes with formation constants similar to other trivalent lanthanides. Crown ethers and cryptands exhibit moderate affinity for Pm³⁺ ions, with selectivity patterns following ionic radius preferences. Organometallic chemistry remains largely unexplored due to synthetic challenges, though cyclopentadienyl and related π-bonded ligands would be expected to form similar complexes to other lanthanides. Complex formation constants typically decrease across the lanthanide series due to increasing charge density, with promethium exhibiting intermediate behavior between neodymium and samarium.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Natural promethium occurs in extremely trace quantities in Earth's crust, with total estimated abundance of approximately 500-600 grams at any given time. This remarkable scarcity results from the absence of stable isotopes and relatively short half-lives of all promethium nuclides compared to geological timescales. The primary natural sources include rare alpha decay of europium-151 to promethium-147 with a half-life of 4.62 × 10¹⁸ years, and spontaneous fission of uranium-238 producing various promethium isotopes. Europium-151 decay accounts for approximately 12 grams of natural promethium in the crustal reservoir, while uranium spontaneous fission contributes roughly 560 grams. Promethium concentrations in naturally occurring ores reach maximum levels of 4 × 10⁻¹⁸ by mass in uraninite (pitchblende), representing one of the lowest elemental abundances in terrestrial materials. Geochemical behavior follows typical trivalent lanthanide patterns when promethium is artificially introduced into natural systems, exhibiting strong affinity for phosphate minerals, clays, and organic matter. The element shows minimal fractionation from other lanthanides during weathering and sedimentary processes, maintaining chondritic relative abundance ratios in most environments.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

Promethium represents the most nuclear-unstable element among the first 84 elements, with 41 known isotopes ranging from ¹²⁶Pm to ¹⁶⁶Pm and 18 nuclear isomers. The isotopic instability arises from the odd atomic number combined with nuclear shell effects that prevent formation of magic number configurations. Promethium-145 exhibits the longest half-life of 17.7 years, decaying primarily via electron capture (99.9997%) with a minor alpha decay branch (2.8 × 10⁻⁷ %) to praseodymium-141. The specific activity of ¹⁴⁵Pm reaches 5.13 TBq/g (139 Ci/g), indicating high radioactivity levels. Promethium-147 serves as the most technologically important isotope with a half-life of 2.62 years, decaying via beta-minus emission to stable samarium-147 with maximum beta energy of 224 keV. Other significant isotopes include ¹⁴⁴Pm (363 days, electron capture), ¹⁴⁶Pm (5.53 years, electron capture), and ¹⁴⁸mPm (43.1 days, internal transition). Nuclear decay modes vary systematically with mass number: lighter isotopes undergo electron capture and positron emission, while heavier isotopes decay via beta-minus emission. Several promethium isotopes exhibit theoretical alpha decay possibilities, though only ¹⁴⁵Pm shows experimentally observed alpha emission with partial half-life of 6.3 × 10⁹ years.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Industrial promethium production relies exclusively on artificial synthesis methods due to negligible natural abundance. The primary production pathway involves thermal neutron bombardment of uranium-235 in nuclear reactors, yielding promethium-147 as a fission product with approximately 2.6% yield. Oak Ridge National Laboratory historically produced up to 650 grams annually during peak production periods in the 1960s through specialized uranium fuel processing and fission product separation. Ion-exchange chromatography using chelating resins provides the most effective purification method, exploiting subtle differences in complex formation constants among lanthanides. Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) serves as an effective eluant, achieving separation factors of 1.5-2.0 between promethium and neighboring lanthanides. Alternative production methods include proton bombardment of uranium carbide targets in particle accelerators and neutron activation of enriched neodymium-146. Solvent extraction techniques using tributyl phosphate or bis(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid enable concentration and purification from dilute fission product solutions. Electrochemical reduction of promethium fluoride with lithium metal at 1100°C produces metallic promethium according to the reaction PmF₃ + 3Li → Pm + 3LiF. Current global production capacity remains limited to research quantities, with Russia maintaining the only significant production facility since U.S. operations ceased in the early 1980s.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

Promethium-147 applications exploit its favorable nuclear decay characteristics: moderate half-life, pure beta emission, and low penetrating radiation. Luminous paints incorporate promethium-147 with zinc sulfide or similar phosphors, providing self-luminous capability for emergency signage, watch dials, and instrument panels. These systems deliver stable light output for several years without external power, superior to radium-based alternatives due to reduced health hazards and phosphor degradation. Atomic batteries utilize promethium-147 beta particles to generate electrical current through semiconductor junctions, typically producing milliwatt power levels with operational lifetimes of 5-10 years. The first promethium atomic battery, constructed in 1964, generated several milliwatts from a 2-cubic-inch volume including shielding. Thickness measurement applications employ promethium-147 sources to gauge material thickness by measuring transmitted radiation intensity, providing non-contact measurement capability for industrial quality control. Potential future applications include portable X-ray sources for medical and security applications, auxiliary power systems for remote sensors and space missions, and specialized nuclear batteries for medical implants. Economic constraints limit widespread adoption due to high production costs, estimated at $1000-5000 per gram for high-purity promethium-147. Environmental considerations favor promethium over alternative radioisotopes due to moderate half-life, low-energy radiation, and absence of long-lived decay products.

Historical Development and Discovery

The discovery of promethium represents one of the most protracted element searches in chemical history, spanning from theoretical prediction to laboratory isolation over four decades. In 1902, Czech chemist Bohuslav Brauner observed unusually large property differences between neodymium (element 60) and samarium (element 62), suggesting an intermediate element. Henry Moseley's pioneering X-ray spectroscopy studies in 1914 confirmed the missing element 61 by identifying systematic gaps in atomic number sequences. Multiple false discoveries plagued the search, beginning in 1926 with Luigi Rolla and Lorenzo Fernandes claiming isolation of "florentium" from Brazilian monazite, and Smith Hopkins and Len Yntema announcing "illinium" from University of Illinois research. Both claims were subsequently disproven when the observed spectral lines were attributed to didymium and various impurities rather than element 61. Josef Mattauch's formulation of the isobar rule in 1934 provided theoretical justification for the absence of stable element 61 isotopes, explaining the unsuccessful terrestrial searches. A partially successful experiment by H.B. Law at Ohio State University in 1938 produced radioactive nuclides that were likely promethium isotopes, but lacked definitive chemical identification. The definitive discovery occurred in 1945 at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (then Clinton Laboratories) when Jacob Marinsky, Lawrence Glendenin, and Charles Coryell isolated and characterized promethium from uranium fission products using ion-exchange techniques. The researchers initially proposed "clintonium" after their laboratory, but ultimately adopted "prometheum" suggested by Grace Mary Coryell, later modified to "promethium" for consistency with other metal names. The first metallic promethium sample was produced in 1963 through lithium reduction of promethium fluoride, enabling measurement of fundamental physical properties and completing the characterization of element 61.

Conclusion

Promethium occupies a unique position among the elements as the only lanthanide lacking stable isotopes, representing a singular example of nuclear instability within the rare earth series. The element's discovery resolved the last remaining gap in the first 84 elements of the periodic table and demonstrated the power of nuclear chemistry in producing previously unknown materials. Promethium's chemical behavior exemplifies typical lanthanide characteristics while providing insights into f-block electronic structure and bonding. The element's technological applications, though specialized, demonstrate practical utility of radioactive materials in energy generation and measurement systems. Future research opportunities include development of more efficient production methods, exploration of novel coordination complexes, and investigation of potential medical applications. Understanding promethium's nuclear properties contributes to broader knowledge of nuclear stability and synthesis pathways for superheavy elements. The element serves as a testament to the intersection of theoretical prediction, experimental discovery, and practical application in modern chemistry and nuclear science.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.