| Element | |

|---|---|

88RaRadium226.02542

8 18 32 18 8 2 |

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 88 |

| Atomic weight | 226.0254 amu |

| Element family | Alkali earth metals |

| Period | 7 |

| Group | 2 |

| Block | s-block |

| Discovery year | 1898 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

| None |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 5.5 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | 700 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Boiling | 1140 °C |

Helium (He) -268.9 Tungsten (W) 5927 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| Oxidation states | +2 |

| First ionization potential | 5.278 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | 0.100 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Electronegativity | 0.9 |

Cesium (Cs) 0.79 Atomic fluorine (F) 3.98 | |

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 8, 2 |

| Electronic configuration | [Rn] 7s2 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 2 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

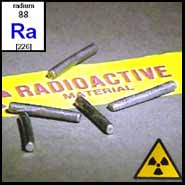

Radium (Ra): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

Radium (Ra, atomic number 88) represents the heaviest naturally occurring alkaline earth metal and the sole radioactive member of group 2 in the periodic table. This highly radioactive element exhibits characteristic metallic properties with a silvery-white appearance that rapidly oxidizes upon air exposure. Radium demonstrates unique radioluminescent properties due to its alpha decay process, which historically led to widespread applications in self-luminous paints and medical treatments. The element possesses a density of 5.5 g/cm³, melting point of 696°C, and crystallizes in a body-centered cubic structure. All known isotopes of radium are radioactive, with Ra-226 being the most stable with a half-life of 1,600 years. Natural occurrence is extremely limited, found primarily as a decay product in uranium and thorium ore deposits. Modern applications are restricted to specialized nuclear medicine procedures due to significant radiological hazards associated with both the element and its immediate decay products.

Introduction

Radium occupies a singular position within the alkaline earth metals as the only radioactive member of group 2, located at atomic number 88 in the seventh period of the periodic table. The element's electronic configuration [Rn]7s² places it directly below barium and establishes its characteristic chemical behavior through the presence of two valence electrons in the outermost s-orbital. Radium's discovery in 1898 by Marie and Pierre Curie marked a pivotal moment in radioactivity research and nuclear chemistry development. The element exhibits the expected periodic trends of increasing atomic radius and decreasing ionization energy relative to lighter group 2 congeners, while simultaneously displaying unique properties associated with its pronounced radioactivity. Natural radium occurs exclusively as decay products within the uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232 decay series, with extremely low crustal abundance necessitating specialized extraction techniques. The element's high specific activity and associated radiation hazards have largely eliminated its commercial applications, though it remains significant in nuclear medicine and fundamental nuclear physics research.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Radium's atomic structure consists of 88 protons and typically 138 neutrons in its most stable Ra-226 isotope, yielding an atomic mass of 226.0254 atomic mass units. The electronic configuration [Rn]7s² indicates complete filling of all inner electron shells through radon's noble gas core, with two electrons occupying the seventh principal energy level s-orbital. This configuration produces an effective nuclear charge experienced by valence electrons of approximately +2.2, accounting for significant shielding effects from the extensive inner electron cloud. Atomic radius measurements indicate a value of 215 pm for the metallic radius, representing the largest atomic size within the alkaline earth metal group and consistent with periodic trends. The ionic radius of Ra²⁺ measures 148 pm, demonstrating substantial contraction upon loss of the two valence electrons and formation of the stable dipositive cation. First and second ionization energies are 5.279 eV and 10.147 eV respectively, reflecting the relatively low binding energy of the valence electrons and the significant energy required to remove electrons from the resulting Ra²⁺ ion.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

Pure radium displays a characteristic silvery-white metallic luster that rapidly darkens upon atmospheric exposure due to surface oxidation reactions. The element exhibits a pronounced tendency to form radium nitride (Ra₃N₂) rather than oxide when exposed to air, producing the characteristic black surface coating observed on metallic samples. Crystallographic analysis reveals a body-centered cubic structure at standard temperature and pressure, with a lattice parameter corresponding to Ra-Ra bond distances of 514.8 pm. This structural arrangement matches that of barium and represents the thermodynamically stable phase under ambient conditions. Radium demonstrates a density of 5.5 g/cm³, the highest among the alkaline earth metals and consistent with the expected increase in atomic mass within the group. Thermal properties include a melting point of 696°C (969 K) and boiling point of 973°C (1246 K), both values falling below those of barium and indicating the continuation of periodic trends despite the element's radioactive nature. Heat capacity measurements yield values of approximately 25.0 J/(mol·K) at 298 K, while thermal conductivity approaches 18.6 W/(m·K). The pronounced radioactivity of radium produces continuous self-heating effects, with energy deposition rates of approximately 0.676 watts per gram for Ra-226, sufficient to maintain samples at elevated temperatures relative to ambient conditions.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

The [Rn]7s² electronic configuration establishes radium's chemical behavior through the facile loss of two valence electrons to achieve the stable radon noble gas configuration. This characteristic leads to exclusive formation of the Ra²⁺ oxidation state under normal chemical conditions, with the +2 state representing the thermodynamically favored form in aqueous and solid-state environments. Radium exhibits typical metallic bonding in the elemental state, with delocalized electron density contributing to electrical conductivity and mechanical properties. The element demonstrates strong electropositive character with an electronegativity value of 0.9 on the Pauling scale, indicating pronounced tendency toward electron donation in chemical bonds. Coordination chemistry involves primarily ionic interactions with electronegative species, though some covalent character appears in bonds with highly polarizable ligands. Bond lengths in radium compounds consistently exceed those of lighter alkaline earth analogs, with Ra-O distances typically measuring 2.7-2.9 Å in oxide environments and Ra-halogen bonds extending to 3.0-3.2 Å depending upon the specific halide. The large ionic radius of Ra²⁺ facilitates high coordination numbers, commonly achieving 8-12 coordinate geometries in solid-state structures.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Radium exhibits highly reducing electrochemical behavior with a standard reduction potential of -2.916 V for the Ra²⁺/Ra couple, establishing it as the most electropositive alkaline earth metal. This value indicates exceptionally strong tendency toward oxidation and explains the element's rapid reaction with water and atmospheric constituents. Successive ionization energies demonstrate the characteristic pattern expected for group 2 elements, with the first ionization energy of 5.279 eV reflecting relatively weak binding of the outermost 7s electrons. The second ionization energy of 10.147 eV represents the significantly higher energy required to remove an electron from the resulting Ra⁺ ion, though this value remains accessible under normal chemical conditions. Electron affinity measurements indicate a small positive value of approximately 0.1 eV, consistent with the general trend among alkaline earth metals toward minimal electron acceptance capabilities. Thermodynamic stability of radium compounds varies significantly with the nature of the counterion, with fluorides and sulfates demonstrating particularly high lattice energies due to favorable electrostatic interactions. Standard enthalpy of formation values for common radium compounds include -1037 kJ/mol for RaF₂, -996 kJ/mol for RaO, and -1365 kJ/mol for RaSO₄, reflecting the substantial energy release accompanying Ra²⁺ ion formation and subsequent crystallization.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

Radium forms an extensive series of binary compounds exhibiting typical alkaline earth metal stoichiometry and structural characteristics. The oxide RaO crystallizes in the rock salt structure with significant ionic character, though the compound demonstrates limited stability under atmospheric conditions due to conversion to hydroxide and carbonate phases. Radium fluoride (RaF₂) adopts the fluorite structure characteristic of alkaline earth fluorides, with Ra²⁺ ions occupying cubic coordination sites surrounded by eight fluoride anions. This compound exhibits exceptional thermal stability and low solubility in aqueous media, properties exploited in radiochemical separation procedures. The chloride RaCl₂ crystallizes in the rutile-type structure and demonstrates high hygroscopicity, readily forming hydrated species under ambient humidity conditions. Radium bromide and iodide follow similar structural patterns with increasing ionic character and decreasing lattice energies reflecting the larger halide anion sizes. Sulfate formation produces RaSO₄, which exhibits extremely low aqueous solubility (Kₛₚ = 4.0 × 10⁻¹¹) and serves as a common precipitation form for analytical separations. Radium carbonate (RaCO₃) precipitates readily from alkaline solutions, while the phosphate Ra₃(PO₄)₂ demonstrates similar low solubility characteristics. Ternary compounds include mixed halides and complex sulfates, though these species have received limited systematic investigation due to radiological handling constraints.

Coordination Chemistry and Organometallic Compounds

Coordination complex formation with radium centers primarily involves hard donor ligands capable of favorable electrostatic interactions with the large, highly charged Ra²⁺ ion. Aqueous coordination typically produces the [Ra(H₂O)₈]²⁺ or [Ra(H₂O)₁₂]²⁺ species, depending upon solution conditions and temperature, with water molecules arranged in square antiprismatic or icosahedral geometries respectively. Crown ethers demonstrate particular affinity for Ra²⁺ ions, with 18-crown-6 and larger macrocycles forming stable complexes that enable selective extraction from mixed cation solutions. The large ionic radius facilitates interaction with polydentate ligands such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), though the resulting complexes exhibit lower stability constants compared to smaller alkaline earth analogs. Cryptand ligands provide enhanced selectivity and binding strength, with [2.2.2]cryptand forming exceptionally stable Ra²⁺ complexes suitable for radiochemical applications. Organometallic chemistry of radium remains largely unexplored due to the combination of radioactivity concerns and the highly electropositive nature of the metal, which precludes formation of stable carbon-radium bonds under normal conditions. Limited synthetic work suggests possible formation of Grignard-type species under strictly anhydrous conditions, though such compounds would exhibit extreme reactivity and limited thermal stability.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Radium exhibits an extremely low crustal abundance of approximately 1 × 10⁻¹⁰% by weight, making it one of the rarest naturally occurring elements in the Earth's crust. This scarcity reflects both the element's exclusive formation through radioactive decay processes and the relatively short half-lives of its isotopes compared to geological timescales. Natural radium occurrence is intimately linked to uranium and thorium deposits, where it exists in secular equilibrium with parent radionuclides in the respective decay chains. Primary uranium ores such as pitchblende, carnotite, and autunite contain radium concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 mg Ra per kg of ore, corresponding to approximately one part radium per million parts uranium by activity. Thorium-bearing minerals including thorianite and monazite sands contribute additional radium sources through the thorium-232 decay series, though concentrations are typically lower than those found in uranium deposits. Geochemical behavior of radium closely parallels that of barium due to similar ionic radii and charge density, resulting in coprecipitation in barite (BaSO₄) formations and concentration in sedimentary environments. Marine environments exhibit dissolved radium concentrations of 0.08-0.1 Bq/m³, maintained through continuous input from continental weathering processes and submarine groundwater discharge. Hot springs and geothermal systems often display elevated radium levels due to enhanced leaching of source rocks at elevated temperatures.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

A total of 33 radium isotopes have been identified with mass numbers ranging from 202 to 234, though all exhibit radioactive decay with half-lives spanning from microseconds to millennia. Four isotopes occur naturally as members of the primordial decay chains: Ra-226 (t₁/₂ = 1600 years) from the uranium-238 series, Ra-223 (t₁/₂ = 11.4 days) from uranium-235 decay, Ra-224 (t₁/₂ = 3.64 days) and Ra-228 (t₁/₂ = 5.75 years) both from thorium-232 decay. Ra-226 represents the most abundant and extensively studied isotope, constituting approximately 99.9% of naturally occurring radium and serving as the primary source for industrial applications. This isotope undergoes alpha decay with emission of 4.871 MeV alpha particles, producing radon-222 as the immediate daughter product. The decay process exhibits a specific activity of 1.0 Ci/g (37 GBq/g), sufficient to produce observable radioluminescent effects in phosphor-containing materials. Ra-223 demonstrates particular significance in nuclear medicine applications due to its alpha-emitting decay profile and relatively short half-life, enabling targeted therapeutic protocols with limited long-term radiation exposure. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies reveal that Ra-226 possesses zero nuclear spin, while Ra-223 exhibits a spin-3/2 ground state with associated magnetic moment of +0.271 nuclear magnetons. Neutron capture cross-sections for thermal neutrons approach 36 barns for Ra-226, indicating significant neutron absorption probability and relevance to reactor neutronics calculations.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Industrial radium production historically relied upon large-scale processing of uranium ore concentrates, with extraction yields typically achieving 0.3-0.7 mg radium per metric ton of pitchblende ore processed. The initial extraction process involved digestion of pulverized ore with concentrated sulfuric acid at elevated temperatures, followed by selective precipitation of radium and barium sulfates from the resulting solution. Fractional crystallization techniques enabled separation of radium from the more abundant barium through repeated recrystallization of mixed chloride solutions, exploiting subtle differences in solubility behavior. Marie Curie's original purification methods required processing of several tons of pitchblende residues to isolate decigram quantities of radium compounds, illustrating the extreme dilution of the element in natural sources. Modern separation techniques employ ion exchange chromatography with selective elution protocols to achieve high-purity radium fractions from uranium mill tailings or spent nuclear fuel processing streams. Crown ether extraction provides enhanced selectivity for Ra²⁺ ions over competing alkaline earth species, enabling concentration factors exceeding 10⁴ in single-stage operations. Contemporary production levels remain extremely limited, with global annual production estimated at less than 100 grams per year, sourced primarily from specialized nuclear facilities rather than dedicated mining operations. Purification to reactor-grade specifications requires multiple chromatographic stages to achieve radionuclidic purities exceeding 99.9% and minimize contamination from other alpha-emitting species.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

Historical applications of radium centered upon its unique radioluminescent properties, which enabled development of self-luminous paints for watch dials, aircraft instruments, and emergency signage during the early to mid-20th century. These applications exploited the continuous excitation of zinc sulfide phosphors by alpha radiation from Ra-226, producing sustained green luminescence without external power sources. However, recognition of severe health hazards associated with radium exposure led to discontinuation of most commercial applications by the 1970s, with replacement by safer alternatives such as tritium-activated phosphors. Contemporary medical applications focus primarily upon Ra-223 for targeted alpha therapy in advanced prostate cancer treatment, where the isotope's preferential bone uptake and short range alpha emission provide localized tumor irradiation with minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissue. Research applications include use of Ra-Be neutron sources for neutron activation analysis and nuclear physics experiments, though these sources are being phased out in favor of accelerator-based neutron generators. Specialized applications in nuclear reactor technology involve use of radium-containing sources for reactor startup and neutron flux monitoring, though regulatory constraints limit such usage to specialized facilities. Future prospects for expanded radium applications remain limited by intrinsic radiological hazards and the availability of safer alternatives for most potential uses, with continued relevance primarily in specialized nuclear medicine protocols and fundamental nuclear research applications.

Historical Development and Discovery

The discovery of radium emerged from Marie and Pierre Curie's systematic investigation of radioactive phenomena in uranium-containing minerals, beginning with their 1898 analysis of pitchblende residues exhibiting anomalously high radioactivity levels. Initial separation efforts focused upon identifying the unknown radioactive constituents responsible for activities exceeding those attributable to uranium content alone, leading to the identification of both polonium and radium through careful fractionation studies. The Curies' announcement of radium's discovery on December 26, 1898, to the French Academy of Sciences marked a pivotal moment in nuclear chemistry, though isolation of pure radium metal required an additional twelve years of intensive research. Marie Curie's subsequent dedication to radium purification involved processing over three tons of pitchblende residues to obtain 0.1 grams of pure radium chloride by 1902, work that earned her the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Electrolytic isolation of metallic radium was achieved in 1910 through collaboration between Marie Curie and André-Louis Debierne, utilizing mercury cathode electrolysis of radium chloride solutions followed by mercury distillation. Industrial-scale production began in Austria and the United States around 1913, driven primarily by demand for radioluminescent applications and medical treatments. The element's name derives from the Latin word "radius" meaning ray, reflecting its intense radioactive emissions that captured early investigators' attention. Scientific understanding of radium's nuclear properties evolved gradually through the work of Ernest Rutherford, Otto Hahn, and others who elucidated decay series relationships and established the fundamental principles of radioactive transformation. The recognition of radium's severe health hazards emerged through tragic cases of radium dial painters in the 1920s, ultimately leading to establishment of radiation protection standards and fundamental concepts in occupational health physics.

Conclusion

Radium occupies a unique position among the chemical elements as the heaviest naturally occurring alkaline earth metal and the sole radioactive member of its periodic group. The element's distinctive combination of characteristic group 2 chemical behavior with pronounced radioactivity has shaped its scientific and technological significance over more than a century since its discovery. While radium's historical applications in luminous paints and early medical treatments have been largely discontinued due to radiological hazards, the element continues to contribute to specialized nuclear medicine protocols and fundamental nuclear physics research. Current understanding of radium's properties reflects sophisticated theoretical and experimental investigations spanning atomic structure, nuclear decay processes, and coordination chemistry. Future research directions likely include continued exploration of targeted alpha therapy applications, development of improved separation and purification methodologies, and investigation of potential applications in advanced nuclear reactor systems. The element's extreme rarity and associated handling challenges ensure that radium will remain primarily of scientific rather than commercial interest, serving as a valuable probe for understanding heavy element chemistry and radioactive decay processes in both fundamental and applied nuclear science contexts.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.