| Element | |

|---|---|

1HHydrogen1.0079471

|

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 1 |

| Atomic weight | 1.007947 amu |

| Element family | Non-metals |

| Period | 1 |

| Group | 1 |

| Block | s-block |

| Discovery year | 1766 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

1H 99.985% 2H 0.015% |

1H (99.99%) |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 8.988E-5 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | -258.975 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Boiling | -252.9 °C |

Helium (He) -268.9 Tungsten (W) 5927 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| Oxidation states | -1, +1 |

| First ionization potential | 13.598 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | 0.754 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Electronegativity | 2.2 |

Cesium (Cs) 0.79 Atomic fluorine (F) 3.98 | |

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 1 |

| Electronic configuration | 1s1 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 1 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

Hydrogen (H): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

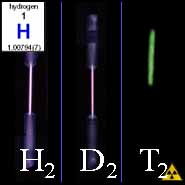

Hydrogen, with atomic number 1 and symbol H, stands as the lightest and most abundant element in the universe, constituting approximately 75% of all normal matter by mass. The element exhibits unique properties derived from its 1s¹ electron configuration, existing primarily as colorless, odorless H₂ gas under standard conditions with a density of 0.00008988 g/cm³. Hydrogen demonstrates dual chemical behavior, forming both positively charged H⁺ ions and negatively charged H⁻ hydride ions. Its first ionization energy of 1312.0 kJ/mol represents the highest per-electron value among all elements. Three naturally occurring isotopes exist: protium (¹H, 99.98% abundance), deuterium (²H), and radioactive tritium (³H). Industrial applications encompass ammonia synthesis, petroleum refining, and emerging fuel cell technologies, with production methods including steam reforming and electrolysis.

Introduction

Hydrogen occupies position 1 in the periodic table, forming the foundation of atomic structure theory and quantum mechanical understanding. The element's singular proton-electron system provides the only exactly solvable atomic model in quantum mechanics, making hydrogen fundamental to theoretical chemistry. Its unique electronic structure, lacking inner electron shells, results in distinctive chemical properties that differentiate hydrogen from all other elements. The element's discovery traces to Henry Cavendish's 1766 isolation of "inflammable air," later named hydrogen ("water-former") by Antoine Lavoisier upon recognizing its role in water formation. Modern applications span from industrial-scale ammonia production via the Haber-Bosch process to advanced fuel cell technologies, positioning hydrogen at the forefront of sustainable energy research.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Hydrogen's atomic structure comprises a single proton nucleus and one electron occupying the 1s orbital. The atomic mass of 1.007947 u reflects contributions from naturally occurring isotopes, with the standard atomic weight ranging from 1.00784 to 1.00811 u. The electron configuration 1s¹ places hydrogen uniquely in the periodic table, as it can achieve noble gas configuration either by losing its electron (forming H⁺) or gaining one electron (forming H⁻ with helium-like 1s² configuration). The covalent radius measures 0.37 Å, while the van der Waals radius extends to 1.20 Å. Effective nuclear charge calculations show minimal shielding effects due to the absence of inner electrons, resulting in strong nuclear attraction of the valence electron.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

Hydrogen gas presents as colorless, odorless, and tasteless under ambient conditions. The element exhibits the lowest density among all gases at 0.00008988 g/cm³ under standard temperature and pressure. Phase transitions occur at extremely low temperatures: melting point at -258.975°C (14.175 K) and boiling point at -252.9°C (20.25 K). The heat of fusion measures 0.117 kJ/mol, while the heat of vaporization reaches 0.904 kJ/mol. Molecular hydrogen demonstrates paramagnetic properties in its triplet ortho form and diamagnetic behavior in its singlet para form. Crystal structure analysis of solid hydrogen reveals hexagonal close-packed arrangement at low pressures, transitioning to face-centered cubic structure under elevated pressure conditions.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

The 1s¹ electron configuration imparts distinctive bonding characteristics to hydrogen. Covalent bond formation typically involves sharing the single electron with other atoms, exemplified by the H-H bond in diatomic hydrogen with dissociation energy of 436 kJ/mol. Bond lengths in hydrogen compounds vary significantly: H-H at 0.74 Å, H-C at approximately 1.09 Å, and H-O at 0.96 Å in water. Hybridization concepts don't apply directly to hydrogen due to the absence of p orbitals, yet hydrogen participates in various bonding arrangements. The element exhibits unusual behavior in forming hydrogen bonds when covalently attached to highly electronegative atoms like oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine, contributing to the unique properties of water and biological molecules.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Hydrogen's electronegativity measures 2.20 on the Pauling scale, placing it between carbon (2.55) and boron (2.04). This moderate value reflects hydrogen's ability to participate in both ionic and covalent bonding modes. The first ionization energy of 1312.0 kJ/mol (13.6 eV) represents the energy required to remove the single electron, forming the bare proton H⁺. Electron affinity data indicates hydrogen's capacity to accept electrons, forming the hydride ion H⁻ with electron configuration 1s². Standard reduction potentials vary with reaction conditions: the H⁺/H₂ couple exhibits E° = 0.000 V by definition, serving as the reference standard for electrochemical measurements. Thermodynamic stability analysis reveals hydrogen's preference for molecular H₂ formation under reducing conditions and proton formation in acidic aqueous environments.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

Hydrogen forms extensive binary compound series with most elements across the periodic table. Metal hydrides encompass ionic compounds like sodium hydride (NaH), where hydrogen exists as H⁻, and interstitial hydrides with transition metals exhibiting metallic bonding characteristics. Covalent hydrides include water (H₂O), ammonia (NH₃), and methane (CH₄), demonstrating hydrogen's versatility in bonding with nonmetals. Hydrogen halides (HF, HCl, HBr, HI) exhibit increasing acid strength down the halogen group, with formation enthalpies ranging from -273 kJ/mol for HF to -26 kJ/mol for HI. Ternary compounds encompass complex systems like ammonium salts (NH₄⁺ compounds) and hydrated ionic crystals, where hydrogen participates in both covalent and hydrogen bonding interactions.

Coordination Chemistry and Organometallic Compounds

Hydrogen coordination occurs primarily through agostic interactions in organometallic complexes, where C-H bonds coordinate weakly to metal centers. Terminal metal hydrides feature direct M-H bonds, while bridging hydrides span multiple metal centers in cluster compounds. Spectroscopic characterization reveals distinctive parameters: ¹H NMR chemical shifts for metal hydrides typically appear between -5 to -25 ppm, significantly upfield from organic protons. Vibrational spectroscopy shows M-H stretching frequencies around 1800-2100 cm⁻¹, distinguishing them from organic C-H stretches near 3000 cm⁻¹. Organometallic hydrogen compounds play crucial roles in catalytic processes, including hydrogenation reactions and C-H activation mechanisms essential for petroleum refining and pharmaceutical synthesis.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Hydrogen constitutes the most abundant element in the universe, accounting for approximately 75% of normal matter by mass and over 90% by number of atoms. Stellar nucleosynthesis produces hydrogen through proton-proton chain reactions, maintaining cosmic abundance. On Earth, free hydrogen gas comprises only 0.00005% of the atmosphere by volume due to its low molecular weight enabling escape to space. Crustal abundance reaches approximately 1520 ppm by weight, primarily bound in water (H₂O), clay minerals, and organic compounds. Geochemical behavior shows hydrogen's preference for hydrated phases and organic matter, with isotopic fractionation occurring during water cycle processes and biological metabolic pathways.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

Three hydrogen isotopes occur naturally with distinct nuclear properties. Protium (¹H) dominates with 99.98% natural abundance, consisting of one proton and zero neutrons, making it the only stable nucleus without neutrons. Deuterium (²H or D) contains one proton and one neutron with atomic mass 2.01355321270 u and natural abundance of approximately 0.0156%. Nuclear magnetic resonance properties differ significantly: protium exhibits nuclear spin I = 1/2 with magnetic moment +2.793 nuclear magnetons, while deuterium shows I = 1 with moment +0.857 nuclear magnetons. Tritium (³H) remains radioactive with half-life 12.32 years, undergoing beta decay to helium-3. Nuclear cross-sections for neutron interactions vary dramatically among isotopes, with deuterium showing lower absorption cross-section than protium, explaining its utility as nuclear reactor moderator.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Industrial hydrogen production relies predominantly on steam reforming of natural gas, accounting for approximately 95% of global production. The process involves endothermic reaction of methane with steam at 800-900°C over nickel catalysts: CH₄ + H₂O → CO + 3H₂, followed by water-gas shift reaction: CO + H₂O → CO₂ + H₂. Alternative production methods include partial oxidation of heavy hydrocarbons, coal gasification, and electrolytic decomposition of water. Electrolysis requires significant electrical energy input (approximately 53 kWh per kilogram of hydrogen) but produces high-purity hydrogen suitable for specialized applications. Purification techniques employ pressure swing adsorption, membrane separation, and cryogenic distillation to achieve purities exceeding 99.999% for semiconductor and electronic applications. Global production capacity exceeds 70 million metric tons annually, with major production centers in China, North America, and the Middle East.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

Current hydrogen applications center on ammonia synthesis for fertilizer production, consuming approximately 60% of global hydrogen supply. Petroleum refining utilizes hydrogen for desulfurization and hydrocracking processes, improving fuel quality and yield. Emerging technologies focus on fuel cell applications, where hydrogen electrochemically combines with oxygen to generate electricity with water as the sole byproduct. Proton exchange membrane fuel cells demonstrate efficiencies exceeding 60% in automotive applications, with power densities approaching 1 kW/L. Hydrogen storage presents ongoing challenges, with methods including high-pressure gas containers (350-700 bar), cryogenic liquid storage, and solid-state metal hydride systems. Economic considerations involve production costs ranging from $1-3 per kilogram via steam reforming to $4-8 per kilogram via electrolysis, with renewable energy integration targeting cost reduction for green hydrogen production.

Historical Development and Discovery

The recognition of hydrogen as a distinct substance emerged from 17th-century investigations of gas evolution from acid-metal reactions. Robert Boyle first observed hydrogen generation in 1671, though without recognizing its elementary nature. Henry Cavendish's systematic studies from 1766-1781 established hydrogen as "inflammable air" with unique properties, including its remarkable lightness and explosive combustion. Antoine Lavoisier's nomenclature contribution in 1783 provided the name "hydrogen" (Greek: water-former) based on combustion experiments demonstrating water formation. The 19th century witnessed fundamental advances in hydrogen spectroscopy, with Johann Balmer's 1885 empirical formula for hydrogen spectral lines later explained by Niels Bohr's 1913 atomic model. Quantum mechanical treatment achieved completion with Erwin Schrödinger's 1926 wave equation solution for the hydrogen atom, establishing the theoretical foundation for modern atomic physics and chemistry.

Conclusion

Hydrogen's position as the first element in the periodic table reflects its fundamental significance in chemistry and physics. The unique 1s¹ electron configuration and minimal nuclear charge create distinctive properties distinguishing hydrogen from all other elements. Its roles in industrial processes, from ammonia synthesis to petroleum refining, demonstrate established economic importance, while emerging applications in fuel cells and energy storage systems position hydrogen as a critical component of sustainable energy infrastructure. Future research directions encompass improved production methods for green hydrogen, enhanced storage technologies, and advanced catalytic applications exploiting hydrogen's unique chemical versatility. The element's dual nature as the simplest atomic system and a complex industrial chemical continues to drive scientific investigation and technological innovation across multiple disciplines.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.