| Element | |

|---|---|

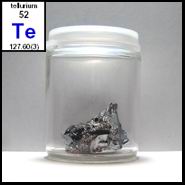

52TeTellurium127.6032

8 18 18 6 |

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 52 |

| Atomic weight | 127.603 amu |

| Element family | Metaloids |

| Period | 5 |

| Group | 16 |

| Block | p-block |

| Discovery year | 1782 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

120Te 0.096% 122Te 2.603% 124Te 4.816% 125Te 7.139% 126Te 18.952% |

122Te (7.75%) 124Te (14.33%) 125Te (21.24%) 126Te (56.39%) |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 6.232 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | 449.65 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Boiling | 990 °C |

Helium (He) -268.9 Tungsten (W) 5927 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| Oxidation states (less common) | -2, +2, +4, +6 (-1, 0, +1, +3, +5) |

| First ionization potential | 9.009 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | 1.971 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Electronegativity | 2.1 |

Cesium (Cs) 0.79 Atomic fluorine (F) 3.98 | |

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 18, 6 |

| Electronic configuration | [Kr] 4d10 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 6 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

Tellurium (Te): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

Tellurium (Te, atomic number 52) is a brittle, mildly toxic, rare silver-white metalloid belonging to the chalcogen group of the periodic table. With a crustal abundance comparable to platinum (~1 μg/kg), tellurium exhibits unique semiconductor properties and forms diverse compounds in oxidation states ranging from -2 to +6. The element demonstrates trigonal crystalline structure, melting point of 722.66 K (449.51°C), and boiling point of 1261 K (987.85°C). Primary industrial applications include cadmium telluride solar cells, thermoelectric devices, and metallurgical alloys for enhanced machinability. Tellurium's extreme terrestrial rarity results from volatile hydride formation during planetary accretion, causing depletion through atmospheric escape mechanisms.

Introduction

Tellurium occupies position 52 in the periodic table as the penultimate member of group 16 (chalcogens), positioned between selenium and polonium. The element exhibits intermediate metalloid characteristics with electronic configuration [Kr]4d105s25p4, featuring four valence electrons in the outermost p orbital. This configuration enables tellurium to manifest diverse oxidation states and form extensive series of binary and ternary compounds. Discovery occurred in 1782 by Franz-Joseph Müller von Reichenstein in Transylvanian gold ore, though systematic identification and nomenclature were completed by Martin Heinrich Klaproth in 1798. The element's name derives from Latin "tellus" meaning earth, reflecting its terrestrial discovery context despite cosmic abundance exceeding rubidium. Modern significance centers on photovoltaic applications, thermoelectric conversion, and specialized semiconductor technologies where tellurium's unique electronic properties provide irreplaceable functionality.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Tellurium exhibits atomic number 52 with standard atomic mass 127.60 g·mol-1, notably exceeding that of iodine (126.90 g·mol-1) despite lower atomic number. The electronic configuration [Kr]4d105s25p4 demonstrates filled d-subshell shielding effects contributing to atomic radius of 140 pm and covalent radius of 138 pm. Effective nuclear charge calculations reveal moderate screening by inner electrons, resulting in first ionization energy of 869.3 kJ·mol-1 and electron affinity of 190.2 kJ·mol-1. Electronegativity values span Pauling scale 2.1, Mulliken scale 2.01, and Allred-Rochow scale 2.01, indicating moderate electron-attracting capability intermediate between selenium (2.55) and polonium (2.0). Successive ionization energies demonstrate characteristic p-block progression: second ionization 1790 kJ·mol-1, third ionization 2698 kJ·mol-1, reflecting progressive removal from filled subshells.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

Crystalline tellurium manifests silvery-white metallic luster in trigonal crystal system (space group P3₁21 or P3₂21 depending on chirality), structurally analogous to gray selenium. The crystal structure consists of parallel helical chains containing three tellurium atoms per turn with interatomic distances of 2.835 Å within chains and 3.49 Å between chains. Density at standard conditions measures 6.24 g·cm-3, reflecting relatively compact packing despite molecular chain structure. Thermal properties include melting point 722.66 K (449.51°C), boiling point 1261 K (987.85°C), heat of fusion 17.49 kJ·mol-1, and heat of vaporization 114.1 kJ·mol-1. Specific heat capacity at 298 K equals 25.73 J·mol-1·K-1. The element exhibits semiconductor behavior with band gap approximately 0.35 eV and demonstrates anisotropic electrical conductivity due to chain-like crystal structure. Photoconductivity occurs upon illumination, indicating electronic excitation across the modest band gap.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

Tellurium's chemical reactivity stems from four valence electrons in the 5p orbital, enabling formation of two covalent bonds with retention of two lone pairs in most compounds. Common oxidation states include -2 in tellurides, +2 in dihalides, +4 in tetrahalides and dioxide, and +6 in hexafluoride and telluric acid derivatives. The +4 oxidation state predominates in terrestrial compounds due to thermodynamic stability considerations. Bond formation typically involves sp³ hybridization producing angular molecular geometries, though higher oxidation states may exhibit octahedral coordination as in TeF₆. Tellurium-oxygen bond lengths range from 1.88 Å in TeO₃²⁻ to 2.12 Å in TeO₄²⁻, reflecting variable bond order and coordination environment. Covalent radii increase with oxidation state: Te⁻² (221 pm), Te⁰ (138 pm), Te⁴⁺ (97 pm), Te⁶⁺ (56 pm), demonstrating systematic electronic contraction upon oxidation.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Standard reduction potentials demonstrate tellurium's intermediate position within the chalcogen series. The Te/Te²⁻ couple exhibits E° = -1.143 V, while TeO₂/Te couple shows E° = +0.593 V in acidic solution. The TeO₄²⁻/TeO₃²⁻ couple displays E° = +1.02 V, indicating strong oxidizing character of tellurate species. Electronegativity progression (O > S > Se > Te > Po) reflects decreasing nuclear attraction with increasing atomic radius. Ionization energy trends follow similar patterns with tellurium showing moderate values intermediate between selenium and polonium. Thermodynamic data for tellurium compounds indicate generally negative formation enthalpies for oxides and positive values for tellurides of electropositive metals. Standard entropy of elemental tellurium equals 49.71 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ at 298 K, consistent with ordered crystalline structure. Bond dissociation energies decrease within the series: H₂O (463 kJ·mol⁻¹) > H₂S (347 kJ·mol⁻¹) > H₂Se (276 kJ·mol⁻¹) > H₂Te (238 kJ·mol⁻¹), reflecting increasing bond length and decreasing orbital overlap.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

Tellurium dioxide (TeO₂) represents the most thermodynamically stable oxide, crystallizing in two polymorphic forms: tetragonal paratellurite and orthorhombic tellurite. Formation occurs via atmospheric oxidation at elevated temperatures, producing characteristic blue flame coloration. The dioxide exhibits amphoteric behavior, dissolving in strong acids to form telluryl compounds and in bases to yield tellurites. Tellurium trioxide (β-TeO₃) forms through thermal decomposition of orthotelluric acid Te(OH)₆, though α- and γ-forms previously reported represent mixed-valence hydroxide species rather than true +6 oxides. Halide chemistry encompasses complete series from fluorides to iodides. Tellurium hexafluoride (TeF₆) adopts octahedral geometry with Te-F bond length 1.815 Å, demonstrating substantial d-orbital participation in bonding. Tetrahalides TeCl₄, TeBr₄, and TeI₄ exhibit square pyramidal structures with stereochemically active lone pairs. Binary tellurides with metals span wide compositional range, from simple 1:1 stoichiometry (ZnTe, CdTe) to complex ternary phases incorporating additional chalcogens or cations.

Coordination Chemistry and Organometallic Compounds

Tellurium forms extensive coordination complexes through utilization of vacant d-orbitals and lone pair electrons. Square planar geometry characterizes tetrahalotellurate anions TeX₄²⁻ (X = Cl, Br, I) with typical Te-X bond lengths 2.5-2.7 Å. Polynuclear species include Te₂I₆²⁻ and Te₄I₁₄²⁻, demonstrating tellurium's capacity for bridging coordination modes. Zintl cations represent unique oxidation products formed in superacid media: Te₄²⁺ (square planar), Te₆⁴⁺ (trigonal prismatic), and Te₈²⁺ (bicyclic structure). These species exhibit distinctive electronic spectra and magnetic properties reflecting delocalized bonding within tellurium frameworks. Organometallic chemistry remains limited compared to lighter chalcogens due to increased Te-C bond lability. Tellurols (R-TeH) demonstrate extreme instability toward hydrogen elimination, while telluraethers (R-Te-R') show enhanced stability through coordination saturation. Tellurium suboxide finds specialized application in phase-change optical storage media, exploiting reversible crystalline-amorphous transitions under laser irradiation.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Tellurium exhibits crustal abundance of approximately 1 μg·kg⁻¹, comparable to platinum and representing one of the rarest stable elements in Earth's crust. This extreme scarcity contrasts sharply with cosmic abundance, where tellurium exceeds rubidium despite the latter's 10,000-fold higher terrestrial concentration. The abundance discrepancy results from volatile hydride formation during early planetary accretion. Under reducing conditions characteristic of the primordial solar nebula, tellurium readily formed hydrogen telluride (H₂Te), which subsequently escaped to space as a gas phase. Selenium experienced similar but less severe depletion through analogous mechanisms. Contemporary geochemical behavior demonstrates chalcophilic and siderophilic tendencies with preferential concentration in sulfide phases and native metal associations. Most tellurium occurs in gold telluride minerals including calaverite and krennerite (AuTe₂), petzite (Ag₃AuTe₂), and sylvanite (AgAuTe₄). Native tellurium crystals occasionally occur but remain geologically uncommon. Industrial extraction predominantly relies on copper and lead refinery anode sludges where tellurium concentrates during electrolytic purification processes.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

Natural tellurium comprises eight isotopes with mass numbers 120, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 128, and 130. Six isotopes (¹²⁰Te through ¹²⁶Te) demonstrate stable nuclear configurations, while ¹²⁸Te and ¹³⁰Te undergo extremely slow radioactive decay via double beta emission and single beta decay, respectively. Isotopic abundances are: ¹²⁰Te (0.09%), ¹²²Te (2.55%), ¹²³Te (0.89%), ¹²⁴Te (4.74%), ¹²⁵Te (7.07%), ¹²⁶Te (18.84%), ¹²⁸Te (31.74%), and ¹³⁰Te (34.08%). The ¹²⁸Te isotope exhibits the longest measured half-life among all radionuclides at 2.2 × 10²⁴ years, exceeding the age of the universe by approximately 160 trillion times. Nuclear magnetic moments range from -0.8885 nuclear magnetons (¹²³Te) to -0.7369 nuclear magnetons (¹²⁵Te) for odd-mass isotopes. Thirty-one artificial radioisotopes exist with masses 104-142 and half-lives ranging from microseconds to 19 days. Notable synthetic isotopes include ¹³¹Te (half-life 25 minutes), important as a precursor for medical iodine-131 production through neutron bombardment. Cross-sections for thermal neutron capture vary significantly: ¹²³Te (418 barns) >> ¹²⁵Te (1.55 barns), enabling selective isotopic activation.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Commercial tellurium recovery occurs as byproduct of copper and lead electrorefinement processes, where tellurium concentrates in anode sludges alongside selenium and precious metals. Typical copper ore processing yields approximately 1 kg tellurium per 1000 tons ore processed, establishing inherent supply limitations. The sludges undergo roasting at 773 K with sodium carbonate under oxidizing atmosphere, converting metal tellurides to sodium tellurite while reducing noble metals to elemental form: M₂Te + O₂ + Na₂CO₃ → Na₂TeO₃ + 2M + CO₂. Leaching with water dissolves hydrotellurites (HTeO₃⁻), which separate from insoluble selenites through selective precipitation with sulfuric acid. The tellurium dioxide precipitate undergoes reduction either electrochemically or through reaction with sulfur dioxide: TeO₂ + 2SO₂ + 2H₂O → Te + 2SO₄²⁻ + 4H⁺. Purification involves zone refining or vacuum distillation producing technical-grade material with 99.5-99.99% purity. Global production reached approximately 630 tonnes in 2022, with China contributing ~54% through both primary mining and secondary recovery. Supply constraints and increasing demand for photovoltaic applications drive price volatility, with values ranging $30-220 per kilogram depending on purity and market conditions.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

Cadmium telluride photovoltaic cells represent the dominant application accounting for approximately 40% of tellurium consumption. These thin-film devices achieve commercial efficiencies exceeding 22% with superior temperature coefficients and low manufacturing costs compared to silicon alternatives. The semiconductor properties of CdTe (band gap 1.45 eV) provide optimal solar spectrum absorption with minimal thermalization losses. Thermoelectric applications consume ~30% of production through bismuth telluride (Bi₂Te₃) compositions exhibiting figure-of-merit values (zT) approaching 1.0 near room temperature. These materials enable solid-state cooling and waste heat recovery in automotive and industrial applications. Metallurgical uses encompass tellurium copper and free-machining steel alloys where small additions (0.04-0.08%) dramatically improve machinability without compromising electrical conductivity or mechanical properties. Emerging applications include cadmium zinc telluride ((Cd,Zn)Te) gamma-ray detectors for medical imaging and astrophysical observations. Phase-change memory technology exploits rapid crystalline-amorphous transitions in tellurium-germanium-antimony compositions for non-volatile data storage. Research frontiers explore rare-earth tritellurides (RTe₃) exhibiting charge-density waves, superconductivity, and topological electronic states with potential quantum computing applications.

Historical Development and Discovery

Tellurium discovery originated from investigations of unusual gold ore from the Mariahilf mine near Zlatna, Transylvania (modern Romania) during the late 18th century. The material, initially designated "antimonalischer Goldkies" (antimonic gold pyrite), confounded mineralogists due to properties inconsistent with known antimony compounds. Franz-Joseph Müller von Reichenstein, serving as Austrian chief inspector of mines, initiated systematic analyses in 1782 concluding the ore contained neither antimony nor bismuth but an unknown metallic substance. Through extensive chemical investigation involving over fifty tests spanning three years, Müller characterized the element's distinctive properties: specific gravity determinations, white smoke evolution with radish-like odor upon heating, red coloration of sulfuric acid solutions, and black precipitate formation upon dilution. Despite comprehensive characterization, Müller could not definitively identify the substance, designating it "aurum paradoxum" (paradoxical gold) and "metallum problematicum" (problem metal). Independent rediscovery occurred in 1789 by Pál Kitaibel investigating similar ore from Deutsch-Pilsen, though credit was appropriately attributed to Müller. Definitive identification and nomenclature were established by Martin Heinrich Klaproth in 1798 following isolation from calaverite mineral. The name "tellurium" derives from Latin "tellus" meaning earth, reflecting terrestrial discovery context. Early applications included Thomas Midgley's investigation of antiknock properties in automotive fuels during the 1920s, though implementation was rejected due to persistent odor effects favoring tetraethyl lead adoption instead.

Conclusion

Tellurium occupies a unique position as the rarest stable element in Earth's crust while simultaneously demonstrating crucial technological significance in modern energy and electronics applications. Its intermediate metalloid properties enable diverse oxidation chemistry spanning -2 to +6 states and formation of complex molecular architectures including Zintl cations and interchalcogen species. Industrial importance centers on photovoltaic energy conversion through cadmium telluride solar cells and thermoelectric waste heat recovery systems utilizing bismuth telluride compositions. Supply limitations arising from byproduct extraction methods and extreme geochemical scarcity present ongoing challenges for expanding technological deployment. Future research directions encompass rare-earth tritelluride quantum materials, advanced thermoelectric composites, and phase-change memory architectures exploiting tellurium's unique electronic switching capabilities. Understanding tellurium's fundamental chemistry and developing sustainable supply chains remain critical for advancing next-generation energy storage and conversion technologies.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.