| Element | |

|---|---|

4BeBeryllium9.01218232

2 |

|

| Basic properties | |

|---|---|

| Atomic number | 4 |

| Atomic weight | 9.0121823 amu |

| Element family | Alkali earth metals |

| Period | 2 |

| Group | 2 |

| Block | s-block |

| Discovery year | 1798 |

| Isotope distribution |

|---|

9Be 100% |

| Physical properties | |

|---|---|

| Density | 1.85 g/cm3 (STP) |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 8.988E-5 Meitnerium (Mt) 28 | |

| Melting | 1278 °C |

Helium (He) -272.2 Carbon (C) 3675 | |

| Boiling | 2970 °C |

Helium (He) -268.9 Tungsten (W) 5927 | |

| Chemical properties | |

|---|---|

| Oxidation states (less common) | +2 (0, +1) |

| First ionization potential | 9.322 eV |

Cesium (Cs) 3.894 Helium (He) 24.587 | |

| Electron affinity | -0.500 eV |

Nobelium (No) -2.33 Atomic chlorine (Cl) 3.612725 | |

| Electronegativity | 1.57 |

Cesium (Cs) 0.79 Atomic fluorine (F) 3.98 | |

| Atomic radius | |

|---|---|

| Covalent radius | 1.02 Å |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 0.32 Francium (Fr) 2.6 | |

| Van der Waals radius | 1.53 Å |

Atomic hydrogen (H) 1.2 Francium (Fr) 3.48 | |

| Metallic radius | 1.12 Å |

Beryllium (Be) 1.12 Cesium (Cs) 2.65 | |

| Compounds | ||

|---|---|---|

| Formula | Name | Oxidation state |

| BeH | Beryllium monohydride | +1 |

| BeSO4 | Beryllium sulfate | +2 |

| BeCl2 | Beryllium chloride | +2 |

| BeI2 | Beryllium iodide | +2 |

| BeO | Beryllium oxide | +2 |

| Be(NO3)2 | Beryllium nitrate | +2 |

| BeF2 | Beryllium fluoride | +2 |

| Be(OH)2 | Beryllium hydroxide | +2 |

| Be3N2 | Beryllium nitride | +2 |

| BeCO3 | Beryllium carbonate | +2 |

| BeH2 | Beryllium hydride | +2 |

| BeBr2 | Beryllium bromide | +2 |

| Electronic properties | |

|---|---|

| Electrons per shell | 2, 2 |

| Electronic configuration | [He] 2s2 |

|

Bohr atom model

| |

|

Orbital box diagram

| |

| Valence electrons | 2 |

| Lewis dot structure |

|

| Orbital Visualization | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Electrons | - |

Beryllium (Be): Periodic Table Element

Abstract

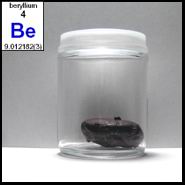

Beryllium (Be, atomic number 4) is a steel-gray, lightweight alkaline earth metal characterized by exceptional mechanical properties and unique chemical behavior. With an atomic mass of 9.0121831 u, beryllium exhibits the highest strength-to-weight ratio among metallic elements, exceptional thermal conductivity (216 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹), and remarkable stiffness with Young's modulus of 287 GPa. The element demonstrates distinctive covalent bonding characteristics atypical of alkaline earth metals, forming predominantly covalent compounds rather than ionic structures. Beryllium occurs naturally in over 100 minerals, with beryl and bertrandite serving as primary commercial sources. The element's low atomic number and density render it transparent to X-rays and neutrons, enabling critical applications in nuclear technology and high-energy physics. Industrial applications capitalize on beryllium's unique combination of low density (1.85 g·cm⁻³), high melting point (1560 K), and superior thermal properties, though commercial utilization requires stringent safety protocols due to the element's established toxicity.

Introduction

Beryllium occupies a distinctive position as the lightest alkaline earth metal in Group 2 of the periodic table, yet exhibits chemical behavior more characteristic of aluminum than its group congeners. The element's unique properties stem from its exceptionally small atomic radius (1.12 Å) and high charge density, resulting in polarizing effects that favor covalent over ionic bonding. The electronic configuration [He]2s² establishes beryllium's divalent nature, though the high ionization energy (9.32 eV for first ionization) prevents simple cation formation. Discovered by Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin in 1798 through chemical analysis of beryl and emerald, beryllium remained a laboratory curiosity until the 20th century when its exceptional mechanical properties were recognized. The element's cosmic abundance is extremely low, approximately 10⁻⁹ relative to hydrogen, reflecting its instability in stellar nucleosynthesis processes. Terrestrial occurrence is similarly restricted, with crustal abundance of 2-6 ppm, concentrated primarily in pegmatitic and hydrothermal deposits. Industrial extraction remains challenging due to beryllium's strong affinity for oxygen and the refractory nature of its compounds.

Physical Properties and Atomic Structure

Fundamental Atomic Parameters

Beryllium's atomic structure exhibits 4 protons, 5 neutrons in the most abundant isotope ⁹Be, and 4 electrons arranged in the ground state configuration 1s²2s². The atomic radius of 1.12 Å represents the smallest value among alkaline earth metals, while the ionic radius of Be²⁺ (0.27 Å in tetrahedral coordination) approaches values typical of highly charged transition metal cations. First ionization energy of 9.32 eV and second ionization energy of 18.21 eV reflect the high electrostatic attraction between electrons and the compact nucleus. Effective nuclear charge values of 1.95 for 2s electrons demonstrate incomplete shielding by the 1s² core, contributing to beryllium's anomalous chemical behavior. Electron affinity (-0.17 eV) indicates thermodynamically unfavorable anion formation, consistent with beryllium's cationic chemistry. The nuclear quadrupole moment of +5.29 × 10⁻³⁰ m² reflects the prolate shape of the ⁹Be nucleus, observable in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Macroscopic Physical Characteristics

Beryllium exhibits steel-gray metallic luster with hexagonal close-packed crystal structure (space group P6₃/mmc) characterized by a = 2.286 Å and c = 3.584 Å lattice parameters. The metal demonstrates exceptional mechanical properties, including Young's modulus of 287 GPa—approximately 35% greater than steel—and ultimate tensile strength reaching 380 MPa in cold-worked conditions. Density of 1.848 g·cm⁻³ at 298 K represents the lowest value among all metals except lithium and magnesium. Melting point occurs at 1560 K (1287°C) with enthalpy of fusion ΔHf = 7.95 kJ·mol⁻¹, while boiling point at 2742 K exhibits enthalpy of vaporization ΔHv = 292 kJ·mol⁻¹. Specific heat capacity of 1925 J·kg⁻¹·K⁻¹ and thermal conductivity of 216 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹ enable exceptional heat dissipation per unit mass. Coefficient of linear thermal expansion (11.4 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹) exhibits remarkably low temperature dependence, contributing to dimensional stability across wide temperature ranges. Sound velocity of 12.9 km·s⁻¹ reflects the combination of high elastic modulus and low density.

Chemical Properties and Reactivity

Electronic Structure and Bonding Behavior

Beryllium's chemical reactivity diverges significantly from typical alkaline earth metal behavior due to its high charge-to-radius ratio and resulting polarizing power. The 2s² valence electrons participate in covalent bonding through sp³ hybridization, forming tetrahedral coordination geometry in most compounds. Electronegativity of 1.57 on the Pauling scale positions beryllium between lithium and boron, reflecting its intermediate metallic-nonmetallic character. Bond enthalpies in beryllium compounds (Be-F: 632 kJ·mol⁻¹, Be-O: 469 kJ·mol⁻¹) exceed values predicted for purely ionic interactions, confirming substantial covalent character. Coordination numbers typically range from 2 to 4, with tetrahedral geometry predominating in solid compounds. The tendency toward polymerization through bridging ligands characterizes beryllium chemistry, exemplified by the chain structure of BeCl₂ and polymeric nature of BeF₂. Coordination expansion beyond tetrahedral geometry occurs only with chelating ligands or under specific conditions.

Electrochemical and Thermodynamic Properties

Standard reduction potential E°(Be²⁺/Be) = -1.847 V establishes beryllium as a strong reducing agent, though kinetic factors often inhibit reduction reactions. Successive ionization energies (9.32 eV, 18.21 eV, 153.9 eV, 217.7 eV) demonstrate the prohibitive energy requirements for oxidation states beyond +2. Electron affinity measurements indicate negligible tendency for anion formation, consistent with beryllium's exclusively cationic chemistry. Hydration enthalpy of Be²⁺ (-2494 kJ·mol⁻¹) reflects the exceptionally strong interaction between the highly charged cation and water molecules. Standard enthalpy of formation values for common compounds (BeO: -609.6 kJ·mol⁻¹, BeCl₂: -490.4 kJ·mol⁻¹) indicate high thermodynamic stability. The amphoteric nature of beryllium oxide enables dissolution in both acidic and strongly alkaline solutions, demonstrating the element's intermediate position between metals and nonmetals.

Chemical Compounds and Complex Formation

Binary and Ternary Compounds

Beryllium oxide (BeO) exhibits wurtzite crystal structure with exceptional thermal conductivity approaching metallic values (260 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹) and melting point of 2851 K. The compound demonstrates amphoteric behavior, dissolving in acids to form hydrated Be²⁺ species and in concentrated alkali to produce beryllate anions. Halide compounds exhibit varying structural motifs: BeF₂ adopts quartz-like structure with corner-sharing tetrahedra, while BeCl₂ and BeBr₂ form polymeric chains with edge-sharing tetrahedral coordination. Beryllium sulfide (BeS), selenide (BeSe), and telluride (BeTe) crystallize in zinc blende structure, demonstrating increasing covalent character with heavier chalcogens. Nitride formation yields Be₃N₂ with high melting point (2473 K) and ready hydrolysis to ammonia and beryllium hydroxide. Carbide Be₂C exhibits refractory properties and distinctive brick-red coloration, undergoing hydrolytic decomposition to produce methane. Boride compounds span compositions from Be₅B to BeB₁₂, reflecting the electronic flexibility of boron-beryllium interactions.

Coordination Chemistry and Organometallic Compounds

Beryllium coordination compounds preferentially adopt tetrahedral geometry with coordination numbers limited by steric and electronic factors. Aqueous coordination forms the stable [Be(H₂O)₄]²⁺ species, though hydrolysis produces trimeric [Be₃(OH)₃(H₂O)₆]³⁺ aggregates at elevated pH values. Fluoride complexing generates a series of stable anionic species: [BeF₃]⁻, [BeF₄]²⁻, with formation constants reflecting the high charge density of Be²⁺. Chelating ligands form particularly stable complexes due to the entropy advantage of bidentate coordination. Organometallic chemistry encompasses alkyl, aryl, and cyclopentadienyl derivatives, typified by beryllocene (Cp₂Be) with η¹-bonding mode and dimeric structure in solid state. Recent developments include the synthesis of diberyllocene featuring the first authenticated Be-Be bond, formally containing beryllium in the +1 oxidation state. Organoberyllium compounds exhibit extreme air and moisture sensitivity, requiring stringent handling procedures. Catalytic applications have been explored for polymerization reactions, though toxicity concerns limit practical implementation.

Natural Occurrence and Isotopic Analysis

Geochemical Distribution and Abundance

Beryllium exhibits crustal abundance of 2-6 ppm, concentrated primarily in felsic igneous rocks and associated pegmatitic deposits. Geochemical behavior reflects the element's incompatible character during magmatic differentiation, leading to enrichment in late-stage fractionation products. Principal ore minerals include beryl (Al₂Be₃Si₆O₁₈) in pegmatites and bertrandite (Be₄Si₂O₇(OH)₂) in hydrothermal deposits. Geographic distribution centers on major pegmatite provinces: Brazil, Madagascar, Russia, and the United States contribute the majority of world reserves exceeding 400,000 tonnes. Marine concentrations remain extremely low at 0.2-0.6 parts per trillion, reflecting minimal solubility of beryllium compounds under oceanic conditions. Atmospheric abundance traces at parts per billion levels, primarily from cosmic ray spallation processes. Soil concentrations reach maximum values of 6 ppm in residual deposits where beryllium-bearing minerals resist weathering. Stream water typically contains 0.1 ppb beryllium, indicating limited mobility under surface conditions.

Nuclear Properties and Isotopic Composition

Natural beryllium consists entirely of the stable isotope ⁹Be (nuclear spin 3/2⁻), making it unique among elements with even atomic numbers as the only stable monoisotopic species. Nuclear binding energy of 58.17 MeV corresponds to 6.46 MeV per nucleon, relatively low compared to nearby nuclides. Cross-section for thermal neutron absorption (9.2 millibarns) enables applications in neutron moderation and reflection. The (n,2n) reaction threshold at 1.9 MeV produces ⁸Be, which promptly decays to two alpha particles with half-life of 6.7 × 10⁻¹⁷ seconds. Alpha bombardment yields the nuclear reaction ⁹Be(α,n)¹²C, historically significant in neutron source technology and Chadwick's neutron discovery. Cosmogenic ¹⁰Be forms through spallation of atmospheric oxygen and nitrogen, accumulating in polar ice with half-life of 1.36 million years. This isotope serves as a proxy for solar activity variations and provides chronological dating capabilities for geological samples. Artificial isotopes range from ⁶Be to ¹⁶Be, with ⁷Be (half-life 53.3 days) notable for electron capture decay and applications in cosmogenic studies.

Industrial Production and Technological Applications

Extraction and Purification Methodologies

Industrial beryllium extraction begins with ore concentration through flotation or magnetic separation to achieve 10-15% BeO content. Thermal processing involves sintering beryl concentrate with sodium fluorosilicate at 1043 K, forming soluble sodium fluoroberyllate and insoluble aluminum oxide. Alternative melting procedures heat beryl to 1923 K followed by rapid quenching and sulfuric acid leaching at 523-573 K. Purification proceeds through precipitation of beryllium hydroxide using ammonia, followed by conversion to fluoride or chloride salts. Reduction to metallic beryllium employs magnesium reduction of BeF₂ at 1273 K or electrolysis of molten BeCl₂. Vacuum casting and electron beam melting produce high-purity ingots with 99.5-99.8% beryllium content. Global production capacity centers in the United States (70%), China (25%), and Kazakhstan (5%), with annual output of approximately 230 metric tonnes. Economic factors reflect high extraction costs due to refractory ore treatment and stringent safety requirements for toxic material handling.

Technological Applications and Future Prospects

Aerospace applications exploit beryllium's unique combination of low density, high stiffness, and thermal stability in satellite structures, missile components, and spacecraft heat shields. The element's transparency to X-rays enables critical applications in medical imaging equipment, synchrotron radiation facilities, and particle physics detectors. Nuclear technology utilizes beryllium as neutron moderator and reflector in research reactors, benefiting from low neutron absorption cross-section and efficient scattering properties. Beryllium-copper alloys (1.8-2.0% Be) provide non-sparking tools for hazardous environments while maintaining high strength and electrical conductivity. Electronic applications include heat sinks for high-power semiconductors and acoustic transducers utilizing beryllium's exceptional sound velocity. Optical systems employ beryllium mirrors in space telescopes where weight reduction and thermal stability prove critical. Future developments focus on powder metallurgy techniques for near-net-shape manufacturing and additive manufacturing processes for complex geometries. Environmental remediation technologies investigate beryllium recovery from industrial waste streams to address supply chain sustainability concerns.

Historical Development and Discovery

The discovery of beryllium originated from Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin's 1798 analysis of beryl and emerald minerals, revealing a previously unknown "earth" distinct from alumina. Initial naming as "glucina" reflected the sweet taste of beryllium salts, later changed to "beryllium" by Friedrich Wöhler in 1828 to avoid confusion with the plant genus Glycine. Metallic beryllium isolation proved challenging, with Wöhler and Antoine Bussy independently achieving reduction of beryllium chloride with metallic potassium in 1828, though the resulting powder could not be melted with available techniques. Paul Lebeau's 1898 electrolytic method using molten beryllium fluoride and sodium fluoride produced the first pure samples (99.5-99.8% purity), enabling systematic study of the element's properties. Industrial development accelerated during World War I under Hugh Cooper's direction at Union Carbide and Alfred Stock's German research program. James Chadwick's 1932 neutron discovery experiment employed beryllium targets bombarded with alpha particles from radium decay, establishing the element's role in nuclear physics history. World War II drove rapid production expansion for beryllium-copper alloys and fluorescent lamp phosphors, though toxicity concerns later restricted phosphor applications. Commercial availability of high-purity beryllium metal began in 1957, finally enabling widespread technological applications that had been theoretically recognized for decades.

Conclusion

Beryllium occupies a unique position among metallic elements through its combination of exceptional mechanical properties, distinctive chemical behavior, and specialized industrial applications. The element's anomalous characteristics—covalent bonding tendency, amphoteric oxide behavior, and extreme light weight—distinguish it from typical alkaline earth metals and enable critical technological functions impossible with alternative materials. Industrial applications in aerospace, nuclear technology, and high-energy physics capitalize on beryllium's irreplaceable combination of low density, high strength, and nuclear transparency. Future research directions include sustainable extraction methodologies, advanced alloy development, and novel processing techniques to expand applications while addressing toxicity concerns. The element's continued importance in emerging technologies such as space exploration, quantum physics instrumentation, and high-performance electronics ensures beryllium's enduring significance in modern materials science despite its challenging handling requirements and limited natural abundance.

Please let us know how we can improve this web app.